Misalignment on Things That Matter: Proving the Point

The Things That Matter aren’t clear or aligned in our relationships. This missing empathy is what is inhibiting understanding, preventing the management of differences, and hampering authentic collaboration. All of this – and more – was demonstrated through a recent workshop exercise we ran.

I recently had the pleasure of running a workshop with Sally Guyer of WorldCC as part of WorldCC’s Collaboration Week.

The theme was “Things That Matter: the foundation of authentic and effective collaboration“, and whilst we covered some familiar ground – recapping what we mean by “Things That Matter“, how relationships are struggling, and why – the main focus of the session was an interactive breakout rooms exercise.

In previous webinars, and throughout this site, we have made the case that being clear and aligned on the Things That Matter is crucial for success – especially in relationships.

However, we’ve also relayed how when you ask people at the front line what the Things That Matter are – to their own party, much less the other – you almost always get vague, varied and even contradictory answers.

At that point, we’ve argued that it’s then no wonder that relationships are struggling.

The breakout rooms exercise made this case for us perfectly – it’s not just us saying these things – so let’s see how.

The background

Ahead of the exercise, I made the case that empathy is the foundation of authentic collaboration. I explained how it’s the first link in a “golden chain” of empathy → understanding → alignment → collaboration → trust, and I also suggested that whilst we know empathy is critical (not least in our personal experience), it’s lacking in our commercial relationships.

I then explained how our Three Step Process plugs this gap, finally making it possible to “scale” empathy from the personal level to the organizational level – beginning with establishing empathy through surfacing the Things That Matter: firstly the Things That Matter to your own party, then clarifying what the Things That Matter to the other party are, and finally coming together to agree what to focus on and prioritize.

It sounds simple, but it really isn’t, and nowhere is this made clearer than when looking at the buy- and sell-side of relationships, where we reviewed some WorldCC research that shows just how little understanding and alignment there appears to be between them, e.g.:

- 77% of suppliers question customers’ claims they want to collaborate (95% feel price is their primary driver)

- “Buyer behaviour is driven by a belief that suppliers care most about revenue and margin… Suppliers say that they seek customers who offer opportunity for growth, readiness to innovate and that enhance their reputation”

The exercise

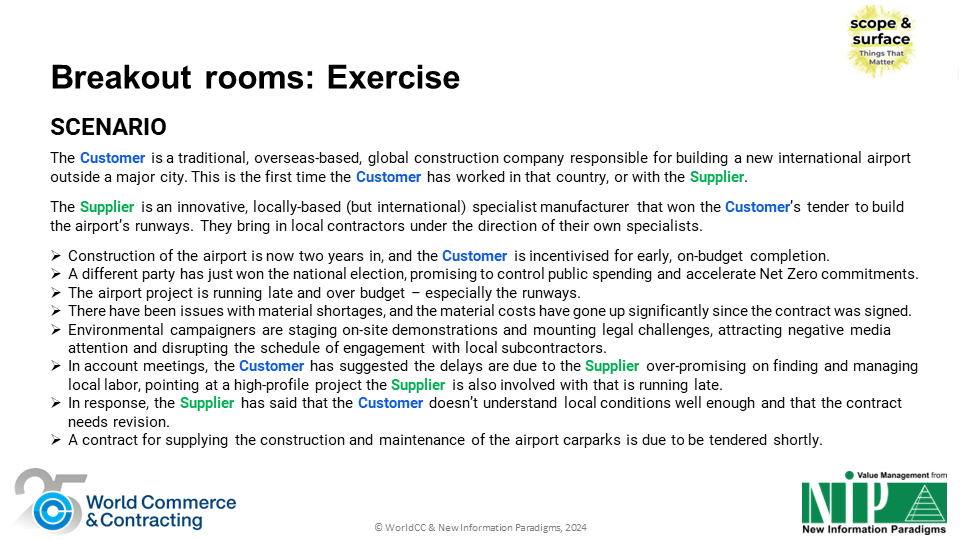

With this in mind, we developed a customer-supplier scenario to illustrate – and for attendees to experience – all of this directly:

You’ll spot how there are various priorities and pressures to juggle, changing external factors, differing perspectives on the situation, and scope for both alignment and divergence.

Having introduced the scenario, attendees were then automatically assigned to be in either a “customer” or “supplier” room, where both were re-presented with the scenario – crucially with some small bits of additional information added – and the instructions guided them through three stages:

- Consider their own perspective – “customer” or “supplier”, as appropriate – and factor out the Things That Matter to them from a combination of what tends to generally be important from that perspective and the specifics of the scenario.

- Switch to consider the other perspective and factor out their likely Things That Matter – again based on what’s generally the case and the specific scenario.

- When presented with what their counterpart room had said, compare and contrast.

This was therefore a chance to explore the following:

- How easy (or otherwise) it is to agree a set of Things That Matter from your own perspective.

- How easy (or otherwise) it is to put yourself in another party’s shoes and consider the Things That Matter to them.

- How closely aligned each party’s actual Things That Matter are with what the other party thinks they are.

- How closely aligned the parties’ Things That Matter are, i.e. even when the parties are clear about what matters to each of them, that doesn’t necessarily mean those Things That Matter align.

The results

Whilst this was of course only an exercise, and there was limited time, I think you’ll agree that the results tell the story extremely effectively.

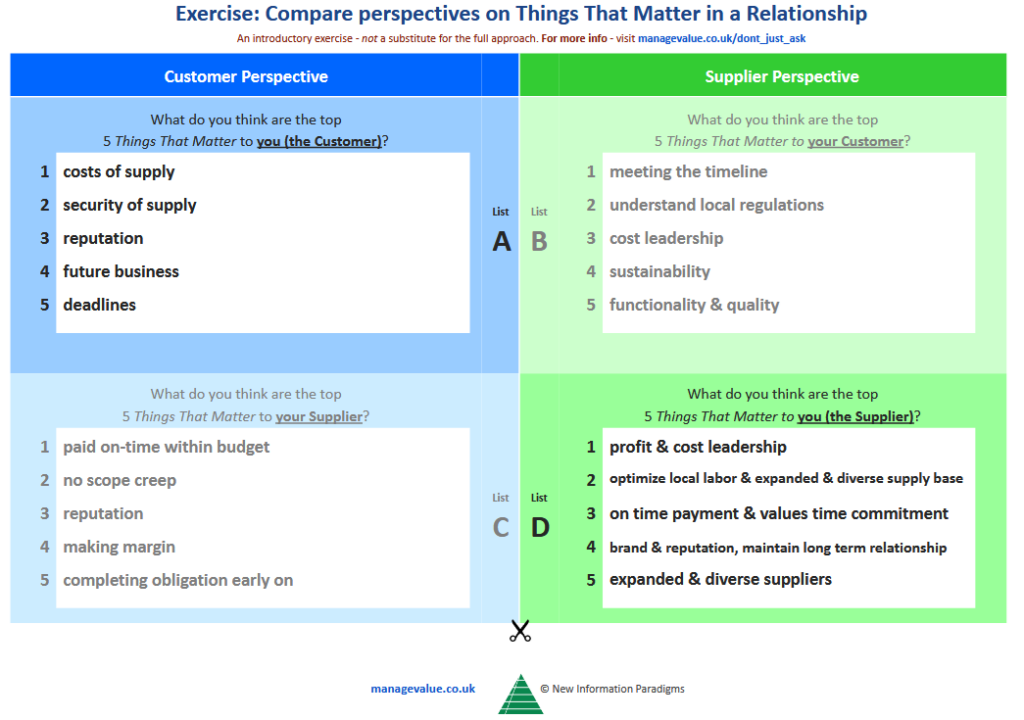

First let’s look at what the “customer” said:

You’ll hopefully already spot some key things:

- How the notes on the right capture and illustrate that there’s a process of gathering different thoughts on what matters, which then require reconciling into a consensus

- How the final order of Things That Matter on the left is often different from the notes: even with brief reflection, a more nuanced sense of priorities emerges

- How cost is usually seen as the top priority

- The scope for clash between the “customer” and “supplier”, i.e. whether the “guesses” about the other party (bottom left) are “accurate” or not, they illustrate a sense of misalignment

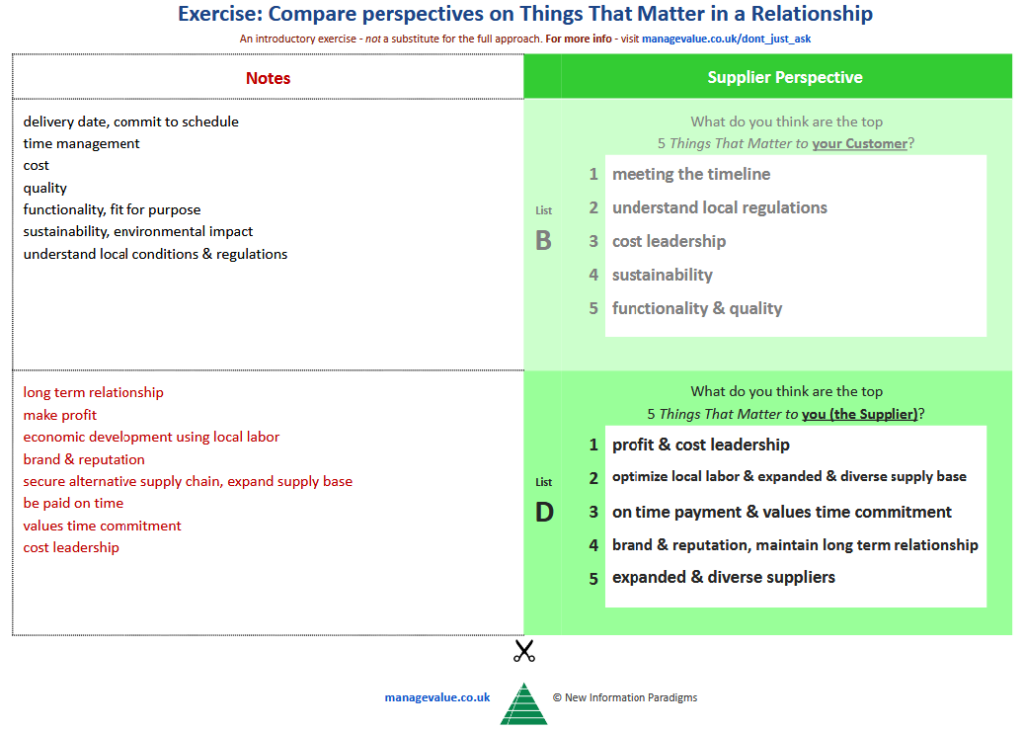

Now let’s look at what the “supplier” said, and we see the same things, further reinforcing them:

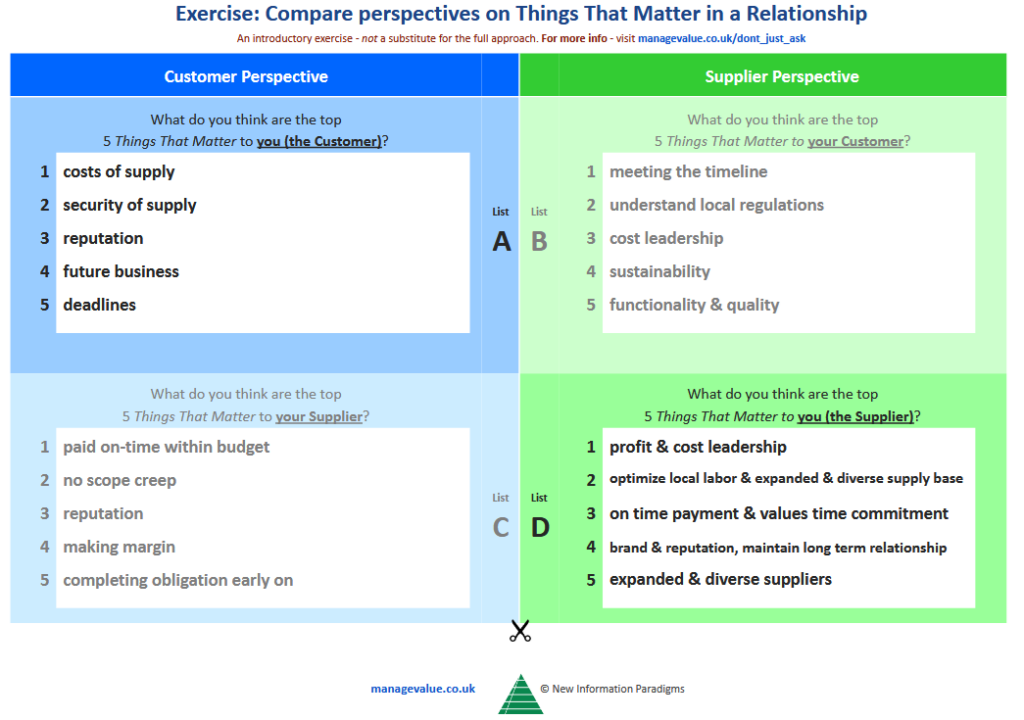

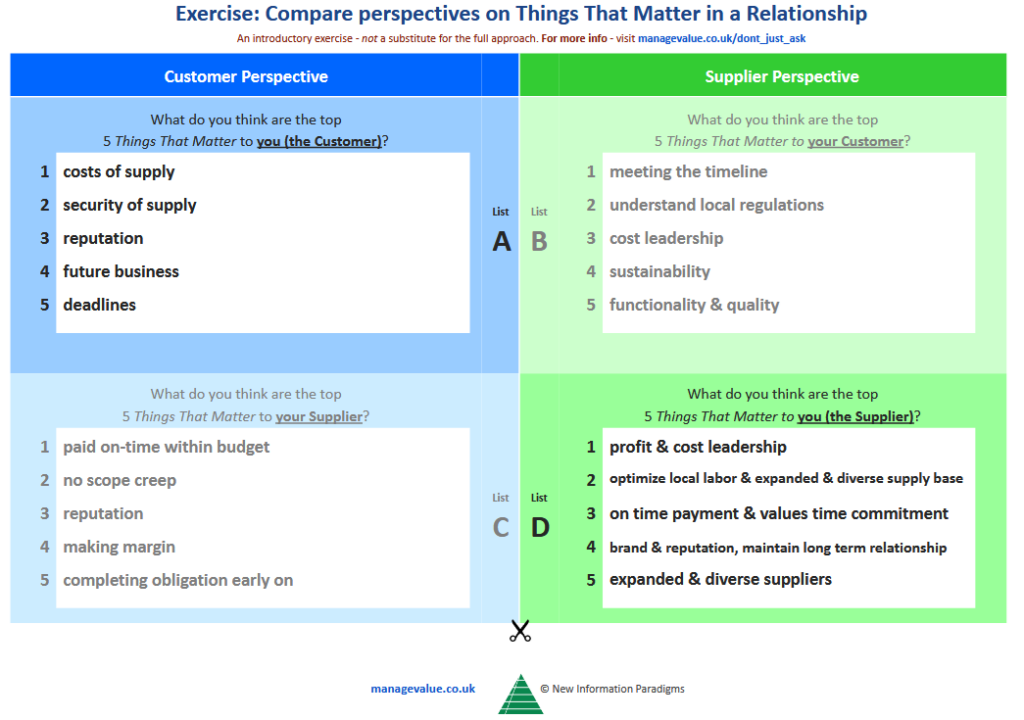

But of course the most striking insights come when putting the four lists of Things That Matter together:

And what do we see? Let’s first compare what the “customer” side said would matter to them (List A) with what the “supplier” thought that would be (List B), and at this point let’s consider that the “customer” was also told:

- The Customer’s new CEO has started an initiative to modernize the company’s image and environmental credentials.

- The Customer is keen to work with an existing contractor for the carparks – one that can deliver reduced whole-life cost.

This of course illustrates that – unless you have these kinds of conversations – there will always be additional factors bearing on the shared relationship, and these things do slightly influence what the “customer” said (3 and 4 in List A), but what’s more obvious is that the “supplier” simply took a different view of the relationship from the “customer”:

- Cost was in both lists, yes, and so were timescales

- However, the prioritization was significantly different for each – especially timescales

- Moreover, the “supplier” assumed two Things That Matter – “understand local regulations” and “functionality & quality” – that the “customer” didn’t pick out at all

- The other way round, the “customer” had “security of supply”, which wasn’t mentioned by the “supplier”.

So, the “supplier” got some of it “right” when thinking about the “customer”, but a lot was at variance.

Let’s now compare what the “supplier” side said would matter to them (List D) with what the “customer” thought that would be (List C), and to save you scrolling, here’s the image again:

Now note that the “supplier” was also told:

- Your colleagues have developed a new all-purpose tarmac: it costs more, but improves durability and reduces dependence on contractors.

- Your colleagues plan to bid for the upcoming car park contract, but suspect they have been pigeon-holed as “the runway people”.

Again, these things had some bearing on “supplier” priorities (4 in List D, and possibly aspects of 2 and 5), but not much, and the differences are again significant:

- Yes, prompt payment, reputation and profitability are in both lists

- Again, though, the prioritization was significantly different

- The “supplier” focus on its own supply base isn’t mentioned by the “customer”

- The other way round, the “customer” thought that “no scope creep” would be important to the “supplier”; it isn’t mentioned by them

And finally, let’s now compare the parties’ stated priorities – list A vs list D – and there’s a similar blend of alignment and divergence:

- There seems to be a mutual concern about the supply chain

- Both are looking at the long-term relationship and are sensitive to reputation

- However, whilst both are concerned about the financials, that’s inevitably from different perspectives

- The “customer” focus on deadlines is potentially at odds with the “supplier” wanting time commitment recognized and valued.

(And let’s not forget that the parties’ priorities weren’t yet clearly understood or aligned – misassumptions and misunderstandings in both directions had already been illustrated, which would in turn make it harder to align around shared priorities and manage differences.)

In the discussion that ensued, it was therefore extremely encouraging to hear participants reflect on how valuable it had been to try and “inhabit” the other party’s perspective.

But there’s more.

The implications

This was of course only an exercise: it involved limited time, a limited number of people and a hypothetical scenario is of course very different from a real relationship.

(Although, in a real relationship, it’s possibly even harder to put yourself in the other party’s shoes – you’re living the reality of any issues, and any assumptions made are likely more entrenched.)

Nevertheless, it illustrated what we’ve been saying:

- People aren’t clear and aligned on what matters in relationships.

- When you ask what the Things That Matter are, it’s hard to do and it involves resolving different perspectives, ideas and priorities.

- You can’t accurately assume what matters to the other party: they will have a different take on the things you do know about; there will be factors on their side that you can’t possibly know.

- There is work to do in clarifying and communicating to your relationship counterparts what matters to you…

- …and that then sets-up the at-least-as-important-task of working out where there are synergies, clashes and differences to accommodate and manage

But even more significant is what such an exercise reveals in terms of what it can’t do:

- Even with a small subset of those involved in a relationship, differing ideas and priorities have come up: what issues and perspectives might be missed by not engaging everyone?

- Even if everyone came away from such an exercise feeling clearer and more enthused, what about those not part of the exercise? Where would their sense of ownership be?

- What might have come up with more time to think than in an exercise like this? What might people not be comfortable sharing in an open forum?

- Whilst an important exercise to illustrate the challenges within the relationship, where was the focus on the end customer in all of this?

Perhaps most of all, what would happen next?

This is why “just asking the question” of what matters isn’t enough – it’s a great start, and an exercise like this can give clear evidence of why the Things That Matter need proper attention, but ultimately such an exercise comes from within the existing ways of doing things:

- It fits naturally within workshops… but these can’t scale.

- It focuses on the relationship… but potentially loses sight of the end customer.

- It helps indicate differences… but doesn’t introduce any new ways of thinking about the situation.

- It suggests that things need to be done… but doesn’t come with any clear next steps.

You need something new.

And that’s where the Three Step Process comes in: to build on any exercise like this by addressing all these challenges of scalability, focus, new insights and – most of all – what to do next.

So, by all means try something like this exercise out, but don’t make the mistake of thinking it will solve anything – indeed, without addressing the challenges I’ve just mentioned, it could even make things worse…!

With the point about misalignment proved, are you ready to try something new, and embark on the Three Step Process?