The Case for Value Management: Part 3: Making It Happen

- Part 1: the Extraordinary Need

- Part 2: the Extraordinary Opportunity

- Part 3: Making it Happen

Pretty much every organization says that Value is a big deal to them. But when you look at what that means in practice, it’s flimsy and disjointed to say the least. What is needed is a dedicated cross-functional Value Management function to put some substance behind the claims of a focus on Value and to deliver on them.

In this final part of this three part series, we’ll see what Value Management transformation looks like and how to make that happen – the people involved, the initial process and then how to spread and scale.

In Part 2 of this series we looked at the extraordinary opportunity there is in focusing on Value for both organizations and the individuals that work in them – especially those stuck in generic, cross-functional roles, for whom Value Management presents a “franchise” for transformed recognition and influence.

We saw how this opportunity provides a compelling vision of the future – motivation for embarking on the always-challenging process of change – and then how existing methods (including short-cuts) simply aren’t able to realize this vision.

Something genuinely new is needed to bring about the necessary transformation.

And, at a high level, more enlightened analysts and practitioners have understood this for some time, e.g. Rick Nason – in his book, It’s Not Complicated – gives a very helpful summary of some guiding principles:

“Consciously managing complexity in a business context is broadly a function of four different strategies or tactics. They are: (1) recognize which type of system you are dealing with; (2) think “manage, not solve”; (3) employ a “try, learn, and adapt” operating strategy; and finally, and perhaps most importantly, (4) develop a complexity mindset.”

But it’s what these four principles looks like in practice that is lacking (which isn’t a criticism of Nason, as this wasn’t his intention).

In Part 2, we dealt with (1) recognizing Complexity and (4) developing the necessary mindset.

But how are this awareness of Complexity and new mindset translated into systematic and sustainable management of Value? Picking up (2) and (3) above:

- What does it look like to “manage, not solve“?

- What tools and approaches comprise the “try, learn and adapt operating strategy”?

In this final part of the series, we will answer these questions by describing a Complexity-aware approach that radically differs from existing methods, actually exists, and which provides all the necessary tools and approaches: Value Management.

Let’s begin with what Value Management transformation looks like – not the results (we did that last time), but the practice itself.

What Value Management transformation looks like

Value Management involves a dedicated group or team taking ownership of Value in the organization, and becoming responsible for modelling a new form of leadership that implements and supports the right conditions for success – guiding outcomes, but not fixing them.

This is achieved through:

- Facilitating the flow of accurate, timely and relevant information to where it is needed – flows of information being not just what catalyses Complexity but also what enables effective responses to it.

- Engaging and harnessing the inputs and expertise of everyone in that organization – people being both the principal cause of Complexity and, through exercising discernment, the uniquely effective force in responding to it.

- Significantly reconceiving the organization as more of a fluid network of self-organized teams that reflect, respond to and harness the ebbs and flows – the emergence – of Complexity, over and above (but complementing) hierarchies.

- Capturing what constitutes Value – the Things That Matter – and articulating it in ways that align people around a common purpose and agenda, and that guide them in acting responsibly, decisively and effectively.

- Fostering the development of situation-specific measures (Value Codes) that guide action; that empower and seed learning (instead of controlling and policing); and that harness the way people most effectively think and operate.

Value Management owes a debt here to the principles of Collective Impact, but it goes further by 1. adding to these principles (especially when it comes to a deep understanding of how people really think and operate), and 2. by systemizing them into consistent, flexible and repeatable meta-processes.

With the latter, this is particularly achieved through appropriately harnessing technology; not indiscriminately continuing to pour its rocket fuel on the flames of Complexity, but instead carefully channeling it to actually power the rocket of transformation.

In this way, technology becomes a servant of people (not the other way round), and not as an end in and of itself – enabling engagement, motivation and change at scale.

For confirmation that this works, just see this short video of Value Management in action: hundreds of people engaged with Value Codes to generate new insights, identify improvement actions, and lead to change.

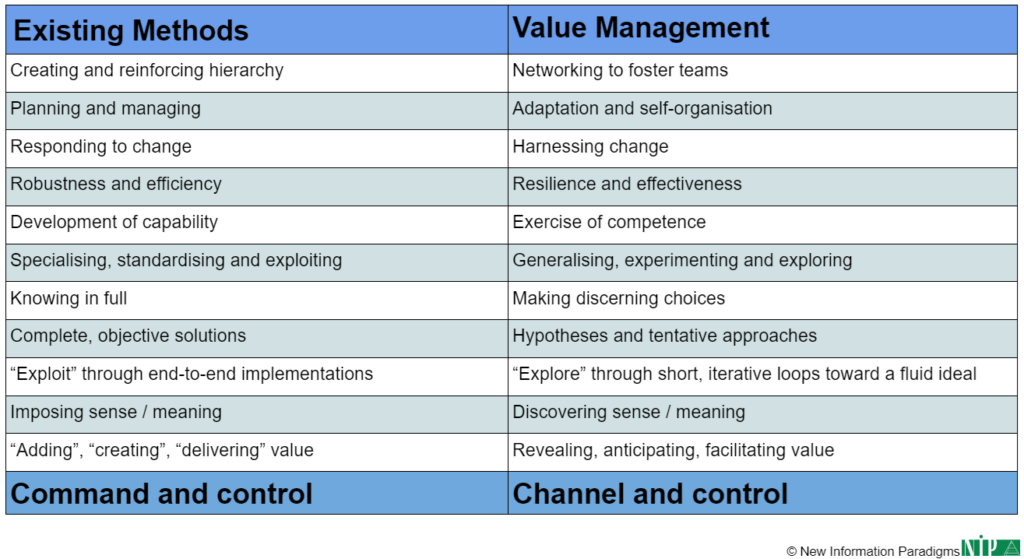

Value Management therefore preserves the best aspects of familiar approaches – leadership, data/information, teamwork, measurement, technology, etc – but fundamentally adapts and reapplies them to realize new goals and qualities:

But if this is the end goal – the vision of what the transformation to a Value Management-led organization looks like – what is the starting point and what are the first steps?

Especially when – as is the case in the vast majority of organizations – things are currently set up in command and control ways that actively work against and resist this kind of transformation?

There are three aspects to consider: the people involved, the initial process followed, and spreading and scaling.

Let’s look at each in turn.

1. The people involved

The most successful Value Management implementations require all of the following three roles to be fulfilled, each of which contributes a different perspective and involves distinct skills in making change happen:

- The change champion – an influential figure who passionately supports, promotes, and drives change, working to overcome resistance and build support across the organization.

- The transformational leader – typically a senior executive with the authority to allocate resources and ensure organizational alignment with the change.

- The change stabilizer – focuses on the logistics and operations of change, ensuring that plans are executed efficiently, on schedule, and within budget.

Consciously considering these roles and who should fulfill them – and when – identifies potential gaps and obstacles, helps ensure accountability, facilitates effective problem-solving and encourages a holistic approach to change.

It may be that the transformation process begins with only one of these roles fulfilled – or one individual straddling a couple of them – but the aim over time is to identify and recruit a nucleus of motivated, passionate and capable individuals that cover all three roles in some configuration, otherwise the Value Management initiative will almost certainly stall for one reason or another.

In practice, whilst the aim over time is for “leadership” to become a behavior that anyone can demonstrate – rather than a position that only a few are appointed to – these roles will often initially be filled by those in existing designated “leadership” roles.

Facilitating the “transition” here is that more familiar hierarchical and “directive” leadership practices will often be effective and appropriate in establishing the Value Management function (after all, there is a bounded scope and limited set of goals for this function, even if the outcomes it seeks to support others in pursuing are totally open-ended, and “top-down” approaches remain ruthlessly effective in tightly limited situations).

But even then, individuals seeking to lead the implementation of Value Management will also need qualities that are typically at odds with what “leadership” is currently thought to involve:

- Accepting uncertainty and “imperfection” in outcomes.

- Acknowledging and embracing that “leaders” don’t (and can’t) know and understand everything and that intuition isn’t a viable means of compensating.

- Acting as a “catalyst”, “facilitator” and “moderator” – helping create autonomy and empowerment for high-performing teams – ahead of the more familiar role of “directing”:

- Allowing others to understand and shape strategy; not just be told what it is.

- Being held accountable to everybody; not just for results but for explaining decisions.

So, what do these individuals now do?

Answering this question involves distinguishing the initial process from what happens when then spreading and scaling.

2. The initial process

Getting started is probably the biggest challenge for would-be proponents of Value Management.

Whilst it’s ideally what organization would have been doing from the outset – we saw in the previous part how atrophy and drift are the inevitable results – the reality in 99.9% of cases is that Value Management is a course correction that is being “retro-fitted”, and this means that pragmatism needs to hold sway.

What this pragmatism looks like in practice is:

- Recognizing that it isn’t practical to simply abandon or “abolish” all that’s gone before (not least because of the huge investments made in it).

- Working as far as possible with existing structures, rather than triggering the corporate “immune system” (e.g. we saw in the previous section how existing leaders are usually the instigators).

- Beginning in a modest, tentative and exploratory way.

- Recognizing that something new needs to prove its worth starting with where the need is most obvious and the potential wins the greatest – in other words, trying to turn around a difficult situation…

- ….and in most cases, this involves an external relationship.

Why? Because another party is involved, which means two things:

- Any fear of there being an internal “witch hunt” or of being put too much under the microscope is immediately deflected or diluted: an external relationship is less “threatening” starting point than something purely internal, which greatly helps buy-in.

- A naturally higher level of Complexity – two parties; not one – and inevitably more challenges: almost nobody feels their relationships are going really well, so the need for change is obvious and the potential wins clear.

The relationship targeted will ideally:

- Be of significant value to both parties so there’s shared motivation to improve.

- Have sufficient time left to run to achieve change.

- Not have any other existing change initiatives in play: you don’t want to overstretch resources.

- Be obviously struggling to all those involved: again, this is where change is most urgent and where success will be most obvious.

The aim is then to engage the relationship’s “community” as widely as possible, and the only way this is possible is with online diagnostics, which bring radical shifts in both content and process – deep, rich and relevant content that is very different from familiar surveys; a motivating and engaging process that can be delivered at scale.

This can (and usually should) start very modestly, though, typically involving some (or even all) of these steps to build engagement, momentum and credibility:

- An individual trialing a diagnostic to expand awareness of what can be evaluated and how its content can be customized if needed.

- A trial group from within the initiating organization using the diagnostic to explore its own (likely divergent) perspectives: in effect, this group is acting as a Value Management function in miniature.

- Using the evidence gathered from initial trials to demonstrate to a wider group and/or the other organization in the relationship the power and novelty of the content and the fragmentation of perspectives that needs uncovering and addressing.

- Using findings to present a business case and secure budget for a wider engagement: if the leaders involved so far don’t yet cover the transformational leader role referenced above, this will involve presenting findings to budget holders.

- Engaging representative participants of all the main perspectives involved in the relationship, including mapping their equivalences for analysis purposes later (e.g. to be able to make observations like “all middle management agreed that…” or “senior leaders were divided about…”).

- Full engagement of the entire community, using the experience and evidence accumulated so far to explain how and why this is something new and entirely deserving of their precious time and attention.

Options exist for which diagnostic to adopt – some are very high-level and open-ended; some are squarely addressed at operational issues – but in all cases, it’s about what will resonate most with the target audience, and all diagnostics will set in motion two parallel processes:

- Our three step process of 1. surfacing the Things That Matter that most define success (but most of which are currently neglected), 2. making them measurable as Value Codes, and then 3, identifying improvement actions.

- Engaging and motivating the community in a new way that shows that change is possible.

The balance of uncovering and clarifying new Things That Matter vs highlighting where progress is needed on those that are already clear will vary, this is always a process of operationalizing empathy at an organizational level – something that just hasn’t been possible to date.

(For more on this, read this article on how the will has been there, but the way simply hasn’t.)

As the process unfolds and expands, any missing change role leaders naturally emerge – either through the passion of their engagement with the diagnostic or by committing to the process when they become aware of it.

The material gathered can be used to advocate for – and demonstrate – the legitimacy, role and value of the embryonic Value Management function.

And, at this point, we enter the spreading and scaling phrase.

3. Spreading and scaling

To demonstrate what is possible in the most challenging circumstances, there can be up to three cycles or classes of diagnostic, which map neatly to the framework proposed as far back as 1981 by Russell L. Ackoff (in his seminal article, “The art and science of mess management”):

- Resolve: understand and address the situation as it is, making its consequences clear, and capturing and exploring a handful of high level Things That Matter to begin with, to diffuse pent up emotions and tensions and hint that something really will change in future.

- Solve: explore and verify the surfaced Things That Matter with richer Value Codes to shift emphasis towards constructive engagement and show that the voice of the community is being heard. (This article explores the discipline of Value Coding in depth, with worked examples.)

- Dissolve: focus on transformational measurement and change using Value Codes derived from, and evolving out of, the second cycle (and then continue to repeat).

This case study describes an example of these three cycles in action in a £1.2bn outsourcing contract, and note that if any stage is neglected or omitted – including, and especially, the repeated iterations of the third step (which is when change really accelerates) – the result will be a loss of engagement and motivation, and a missed opportunity to embed change.

And that’s because, at this stage, there is now a “third step” template for self-reinforcing spreading and scaling:

- A limitlessly-scalable diagnostic platform where new relationships and situations can be effortlessly slotted-in.

- A community of people that have engaged with diagnostic content and the diagnostic process, many of whom will be involved in other relationships and carry that familiarity with them.

- A re-usable version of the process from the previous section that either “worked” first time in terms of securing engagement, commitment and buy-in, or which can now be tweaked as needed.

- A set of Things That Matter, Value Codes and improvement actions that can be offered as a starting point and then adapted for other relationships and situations – each will be unique, but patterns will recur.

- Accumulated knowledge and expertise of how to run the process, how to interpret what it generates, and how to present and use its findings to effect change.

On one level, there being a “template” might seem contradictory given the apparent command and control overtones – after all, templates usually mandate fixed activity top-down; instead, Value Management is instead about bottom-up, collective ownership of Value.

(This being the authentic version of collective ownership compared to the claims we reviewed in Part 1 of “everyone being committed to value“.)

However, the key point is that this is a “meta” template: it’s all about putting in place the underlying conditions – rich information, wide engagement, and how to focus on subjective Value, all appropriately supported by technology – all of which simply reflect the nature of Complex reality and thus how to most effectively harness it…

…but this “template” introduces no “agenda” or content of its own, and is completely agnostic about what Value is defined by – the Things That Matter – in any given situation; all the content comes from those engaged in the process.

And as that process spreads in breadth and depth, so the focus of the Value Management function can expand beyond addressing issues in problematic relationships, and will incorporate:

- The pursuit of more “positive” articulations of Value: culture, values and performance outcomes.

- Benchmarking and the sharing of best practice and learning.

- Portfolio segmentation and management.

Conclusion

At this point, the transformation will have moved away from existing methods and limitations (although transformation itself will continue as long as the organization exists).

The organization will be functioning as a network of dynamically-evolving and high-performing teams; not held together by the rigid hierarchies that currently dominate, but by resilient threads of Value – all connected-to, overseen by and empowered by the Value Management function.

On the individual level, not only will the Value Managers be motivated – not least having found their way out of bullsh!t jobs and narrowly-perceived professions where their skills were wasted and their contribution minimal – but everyone will be working in a more mindful, enthusiastic and interconnected way.

And so, if in Part 1, we saw how organizations inexorably drift away from the entrepreneurial spirit and lose touch with Value and the disasters that follow, we’ve seen in this final part how the expansion of Value Management can wholly reverse that process.

Is it easy? No. Is it both essential and achievable? Yes.