What Value Is: Part 1 – Misunderstood

- Part 1: Value is misunderstood

- Part 2: Value is not properly in focus

- Part 3: Value is understandable, manageable and measurable

“Value”. One of the most frequently-used words in commercial contexts, and we think we all know what it means. But what is “value”, really? Do we understand it? And, if we don’t, what goes wrong? In this series, we’ll show what value really is and, ultimately, why it’s all that matters.

In this first part, we look at how “Value” is significantly misunderstood (and what we lose sight of in the process), and that it’s all that matters – especially when it comes to responding to the challenges we’re all facing.

“Value” is increasingly talked about everywhere in the commercial world.

“Value creation”… “added value”… “value propositions”… “social value”…

And “value” is also becoming official policy.

Here in the UK, for example, the 2023 Procurement Act mentions “value” over fifty times, and in the US, it’s even more direct: a push for “public value outcomes” as part of policy-making.

But what stands out is that value either isn’t really defined – it’s “added”, it’s part of a “proposition”, etc, but what is it?– or it’s immediately (perhaps partly because it’s not otherwise defined) connected to money.

Indeed, here in the UK, we now have a government-appointed Office for Value for Money, and our National Audit Office has produced a planning and spending framework where “Value for Money” is mentioned 109 times!

Back again to the US, and whatever you think of Elon Musk and DOGE, the focus on government spending and whether it’s “value for money” seems here to stay: demands on public finances are only increasing, and it’s of course the same in the private sector, too.

So “value” is everywhere, but what it really means – what it is – remains largely assumed.

And at that point, it’s perhaps not a great surprise that Value is usually significantly misunderstood.

Value is significantly misunderstood

At the heart of these misunderstandings is that, whilst “value” is both a noun and a verb, it’s the noun form that dominates how we consider and talk about Value.

This noun-verb distinction might at first seem trivial, but it really matters, because nouns are largely “things”. And things are fixed and static; they can be pinned-down; controlled.

And so “value” primarily as a noun – as a “thing” – becomes seen as a property of what we’re making or doing, hence “value creation”, and as something that can be worked (hence “added value”).

Even more than that, “value” can then be quantified, hence “value for money”.

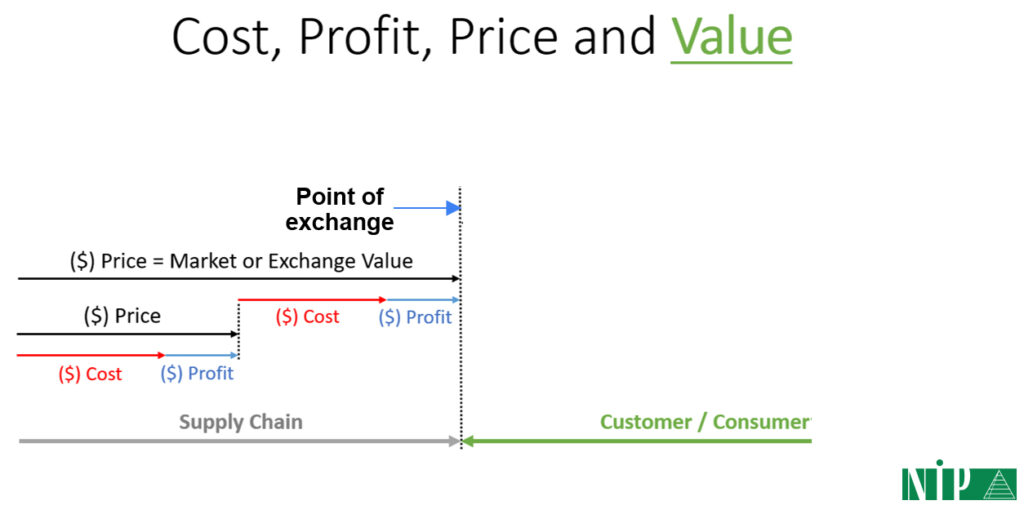

And so the focus ends up being on the supply side:

At the point of exchange, the customer “receives” the Value we’ve produced, as summed up by the concept of “value added tax” – the Value is already there in what’s supplied, and it can be quantified in terms of price and cost.

As a result, what we do, and how we do it – our capabilities, training, and so on – tends to become our primary focus, as the best (perhaps the only) way to lead to Value.

But in the process we lose sight of two crucial things.

What we lose sight of

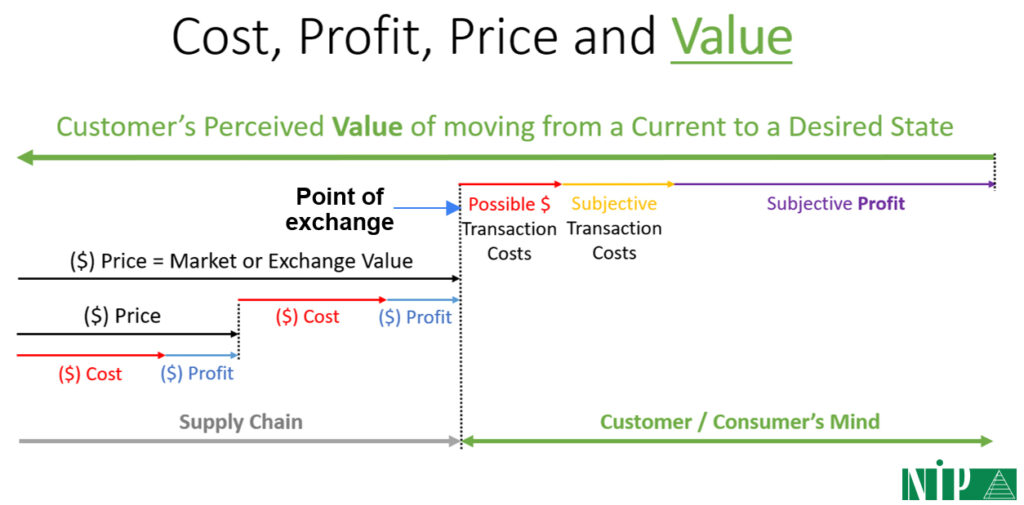

The first thing we lose sight of is how Value flows back from the end customer; not forward from us. Let’s now flesh out the customer or consumer side of our diagram:

We then see that Value spans the whole diagram – not just up to the point of exchange – and that it’s what the customer perceives between their current state and the desired state they want.

Secondly, financials are only part of the scope because, past the point of exchange, Value to the customer is primarily subjective.

In other words, customers only buy when they perceive that the Value they’re getting is more than the price they’re paying: a subjective profit.

And this has two aspects:

- Firstly, perceptions of Value are subjective: they’re the result of a constant, dynamic and fluid valuing process – Value as a verb.

- Secondly, what’s valued is increasingly subjective, too. Think about how services have often overtaken products; how it’s ideas, intangibles and experiences that are often most profitable now; or the emphasis on softer forms of “value”, like sustainability.

A worked example

When a buyer considers purchasing a new house, they encounter a complex web of factors. The builder, for instance, has invested in materials, coordinated suppliers, and employed tradespeople — each “layer” adding its own costs and profit margins, culminating in the final market price of the property. Meanwhile, the buyer incurs their own transaction costs during the search process. These might include tangible expenses like lost earnings, travel, communication, legal fees, and other ancillary charges.

Beyond these financial outlays, though, there are subjective costs to consider — time and effort spent evaluating properties, weighing options, and making decisions about furnishings or other personal touches. Despite these burdens, and if the purchase proceeds, the buyer intends to reap a subjective profit.

This could be significant, driven by their vision of life in the new home—a sense of fulfilment, comfort, or future potential that transcends the monetary price paid. So we can see that the interplay of objective costs and subjective gains shapes the decision, blending measurable expenses with intangible rewards.

And finally, the buyer’s process of “valuing” continues long after the point they move in: at first, for example, when everything is fresh and new, they may perceive the Value of their new house to be very high – including in relation to the price paid. However, when they realize that the school run takes far longer than they thought it would, their neighbors turn out to host band practice every Friday night, and cracks appear in the walls as the fresh plaster “settles”, that perception will become more nuanced.

Putting that all together: without a customer that experiences a sense of subjective profit, there’s therefore no Value, no sales, no supply chain.

What we do, and how we do it, is ultimately only of Value if it leads to the customer experiencing Value.

And Value is ultimately all that matters.

Value is all that matters

On some level, this seems obvious: why would we want to do anything that isn’t valuable?

But to really understand why Value is all that matters, we first need to look at the challenges we’re facing; things like:

- Needing to do more with less (leading to overload, stress, etc)

- The accelerating rate of change (making decisions pressured and rushed)

- Unforeseen external disruption, such as material shortages

- A sense of building on shifting sands, due to growing uncertainty and volatility

- Capability lagging behind, including recruitment / retention issues

- etc, etc

All these flow from Complexity.

There’s lots more detail elsewhere on our site, but Complexity is fundamental to our world.

It’s all about the dynamics of interconnected people and organizations, the subjective decisions they make, and the bottom-up, self-reinforcing change that results.

And technology has now accelerated and fuelled all this to exponential levels: unprecedented interconnectivity; unprecedented interaction between people and organisations (often with very different priorities); and the speed of information, of interaction, and of change has also shot through the roof.

And so Complexity – now particularly fuelled by technology – is the root of the unpredictability, risk and disruption that’s often summarised as PESTLE:

- Political: e.g. (re-)election of Trump, Brexit, etc

- Economic: e.g. inflation crisis, new tariffs, etc

- Social: e.g. ESG, sustainability, etc.

- Technological: e.g. ChatGPT, DeepSeek, etc

- Legal: e.g. diverging regulatory climates, etc

- Environmental: e.g. climate change, etc

All of these pressures (and the impact that they have), reflect Complexity, and that’s then why the familiar VUCA acronym is so misleading – “complexity” isn’t just one factor of four; it’s precisely because of complexity that our world is then “volatile”, “uncertain” and “ambiguous” (such that “C-UVA” would be more accurate, even if less catchy).

Things are only going to get more challenging, and that’s why Value is all that matters: because it’s the only effective response.

Responding to Complexity

Complexity, by definition, can’t be controlled: it’s bottom-up, and unpredictable.

However, we can put in place conditions – or “generative constraints” – that guide and harness Complexity.

They’re “constraints” inasmuch as whenever you put things in place, they set boundaries and exclude other things, but if you get the constraints right, they’re generative: they attract focus and resources; they create momentum towards the outcomes we want.

Complexity then works for us; not against us.

And the main generative constraint needed here is being clear about Value and staying focussed on it.

We’ve already touched on it, but Value is what motivates and engages people.

Moreover, with competing pressures on scarce resources, it’s the ultimate tool for prioritization and gauging how to maximize impact.

As a key part of that, Value provides a catalyst and a focus for the change that Complexity makes inevitable; this change is otherwise the root of disruption, but it can now instead be harnessed as innovation.

From there, we all know how important collaboration is, and many of us work very hard to try and “make” it happen, but clarity and focus around Value – a common goal – instead helps it to emerge naturally.

Interconnectivity, like change, is also part and parcel of Complexity, but again, instead of that just leading to disruption, it’s now harnessed and directed, and this naturally leads to trust (which is of course then critical to the agility, adaptability and resilience that we all need).

But most of all, Value then also reinvigorates and realigns organizations, and it empowers people.

We’ll find out how next time.