When It All Goes Wrong: Part 5: Boeing 737

[Update: since this article was published, where we asked near the end “can we really be confident that anything has really been learned…?”, the Boeing 737 has again been involved in a major incident in January 2024.]

- Introduction

- Part 1: Grenfell

- Part 2: Crossrail

- Part 3: HS2

- Part 4: London Terror Attacks

- Part 5: Boeing 737

In this series, we are looking at a range of situations where the symptoms of Complexity – and of inappropriate responses to Complexity – are particularly striking.

Whilst most Complexity-driven situations (and most of the inappropriate responses made) will never escalate this far, you may well recognise many elements of your own situation in these examples.

Part 5: Boeing 737

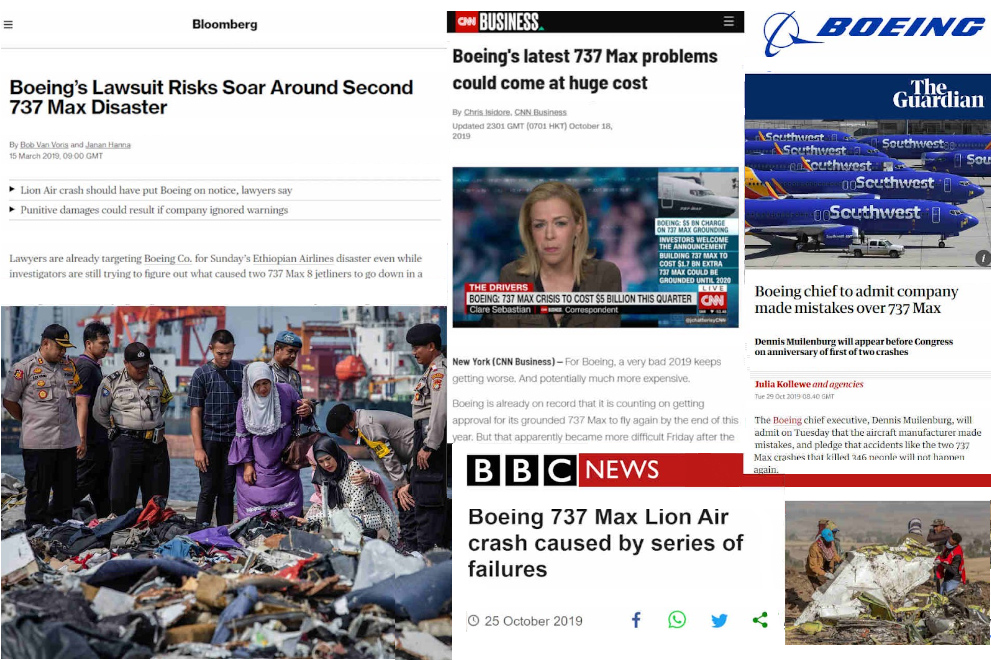

On 29th October 2018, Lion Air flight 610 crashed into the sea shortly after takeoff, killing all 189 people on board.

Less than five months later, Ethiopian Airlines flight 302 crashed even sooner after takeoff, killing all 157 on board.

What united both disasters was the aeroplane involved – the Boeing 737 MAX – the questions subsequently raised about the overlap between the factors involved, and the role that Complexity was shown to have played.

The Role of Complexity

An in-depth BBC article from 17th May 2019 firstly highlighted the aspects of Complexity involved.

To begin with, the launch of the competitor Airbus A320 seemed to have taken Boeing by surprise – surprises and unexpected external disruption being key features of Complexity – and accelerated the rush to market for the 737 MAX.

This rush led to applying a newer engine to an older aircraft, where the design of the latter created tradeoffs with using the former – “This solved one problem, but created another” – with interventions having unexpected consequences being another thing endemic to Complexity.

Later, there were breakdowns in communication between key stakeholders, with airlines and the FAA not informed of the issue that later led to the Lion Air crash – despite over 7500 pilots later found to have been willing to contribute safety information.

Inappropriate Responses

The article also pointed at inappropriate responses to Complexity, both alleged and acknowledged.

In response to the commercial pressure from Airbus, that the decision to “upgrade” the Boeing 737 – rather than design a new aircraft – was a short-sighted pursuit ahead of longer term interests and priorities, where corners were cut due to resource pressures:

“Airlines don’t want to spend money on training if they don’t have to. We’ve seen this with the Boeing 737 Max. It is a different body and aircraft but certifiers gave it the same type rating.”

Furthermore, the article revealed how Boeing was being sued “…by some investors who claim the company concealed problems with the 737 Max and “effectively put profitability and growth ahead of airplane safety and honesty”.

Key information from pilots and testers was either unavailable or ignored – information that could have helped eliminate issues involved in the crashes.

After the Lion Air crash, there was overconfidence – within mere hours after the investigators’ conclusions – that software had solved the problems: a reliance on technology as the “saviour” being an all-too-familiar response to a Complex issue.

Similarly, there was an overreliance on checklists and set procedures as able to cope with issues, “whatever their cause” – when Complexity dictates that what happens frequently defies precedent – and other allegations were that:

- Boeing had used the FAA, the external regulator, to its advantage – lobbying and manipulation of external factors being a common tactic to try and maintain control – in persuading it to allow Boeing to conduct much of the safety testing itself.

- There was a failure to learn lessons – “The trigger for the accident – and the root cause of another crash involving a near-identical 737 Max off Indonesia last year – is thought to have been the failure of a system known as Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS). What now seems apparent with the benefit of hindsight is that MCAS had design flaws. Boeing itself has indicated as much.”.

Although not well-received by victims’ families, there was also debate about how much of the “blame” lies with pilot error.

Regardless of that factor, though, in light of the above it is perhaps little surprise that there were “…further questions about transparency at the aerospace giant – and whether or not it has failed to report any other potential safety concerns”…

Any Lessons Learned…?

…and yet there remained a potential conflicting combination of issues to resolve and commercial pressure for the aeroplane to return to the skies:

- As the BBC reported on 23rd October 2019, the Boeing 737 MAX was still expected to be back in the air before the end of 2019.

- Even though production was later suspended, this was only reported as “Boeing will temporarily halt production…” – later pushed back to July.

- More issues have since been found with, as the BBC reported on 19th February 2020, debris discovered in new planes’ fuel tanks.

So, even if these issues are resolved, can we really be confident that anything has really been learned about the nature of Complex situations and how to respond to them?

[Update: since this article was published, where we asked near the end “can we really be confident that anything has really been learned…?”, the Boeing 737 has again been involved in a major incident in January 2024.]