Value Management: How and Why It Works

Part of the beauty of Value Management is that it just works. But how does it work? And why does it work? Because it is built on the most fundamental foundations – the nature of reality, the nature of value, and the ways our brains work to tie all of this together.

Value Management works.

It’s intuitive and unarguable that everything we do is driven by what we value and the pursuit of realizing that Value.

But just stating this as fact neither explains why it’s the case or then what it means in practice.

To provide that explanation, we’re going to need to do a pretty deep dive – encompassing the nature of reality, the nature of Value, and how it is the human brain that ties it all together.

After nearly 50 years of experience, analysis and reflection around these things, I’d be pretty disappointed if there wasn’t this depth…

…but I’ll warn you upfront: this is rich and dense stuff, it’s not for everyone, and it really is fine to just experience that Value Management works and proceed with confidence from there.

However, if you stick with me, I hope and think you’ll agree it’s worth it, as it begins to indicate the conceptual and practical depth behind Value Management – work we’ve put in so that you don’t have to! – and put some “weight” and “validation” behind the intuition and experience that it works.

The Conceptual Terrain: Polarity

Let’s start with the conceptual terrain, and how reality is defined by (and between) two poles.

Each pole has a force emanating from it that is stronger the nearer you get to it, and operating effectively involves understanding, balancing and managing with dexterity the resulting tensions and dilemmas between the poles.

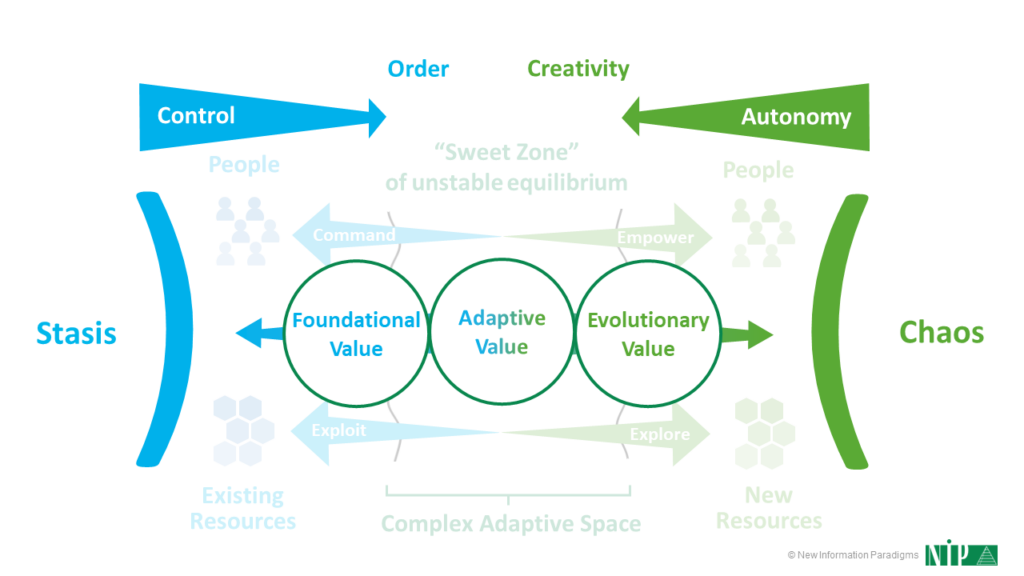

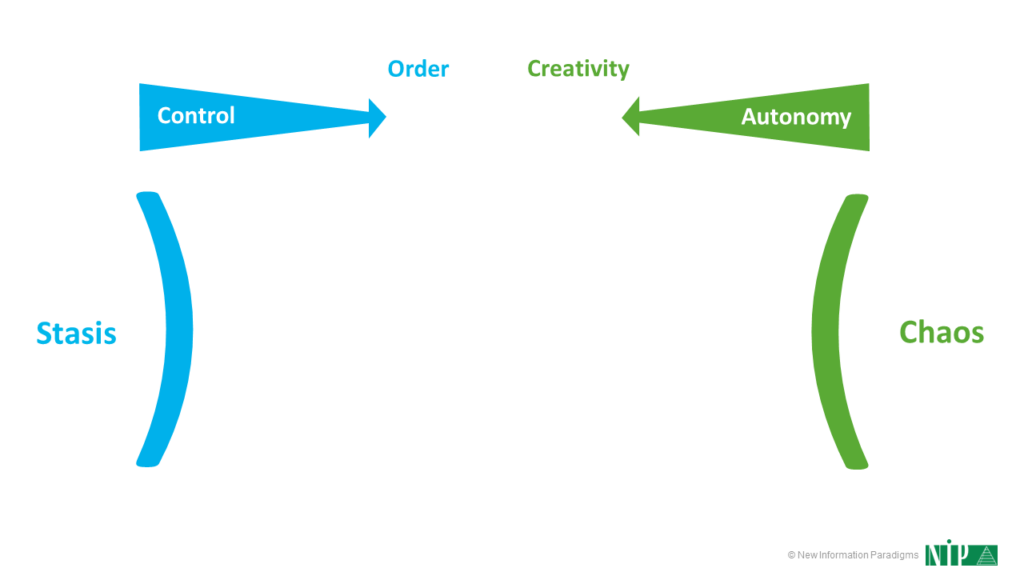

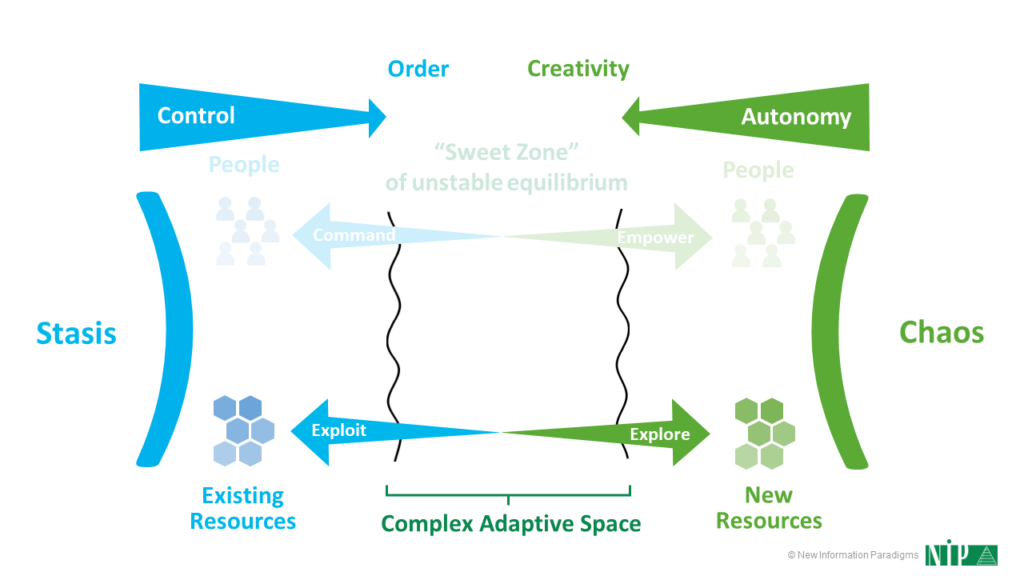

Whether it’s Yin and Yang or the idea in the Genesis account of creation bringing order out of chaos – or a host of others – this concept of polarity is a very ancient idea, and we can represent it like this:

- On the left is Stasis, where nothing changes, and where the force emanating from it is Control, which tends towards Order.

- On the right is Chaos, where everything can change, and where the force emanating from it is Autonomy, which tends towards Creativity.

(At this point, it’s very important to note that Chaos isn’t primarily used here as a “negative”; it’s simply used as the polar opposite of Order, and it’s where all possibilities are open, because there is no fixed structure or Order. Similarly, Order isn’t inherently “positive”, either!)

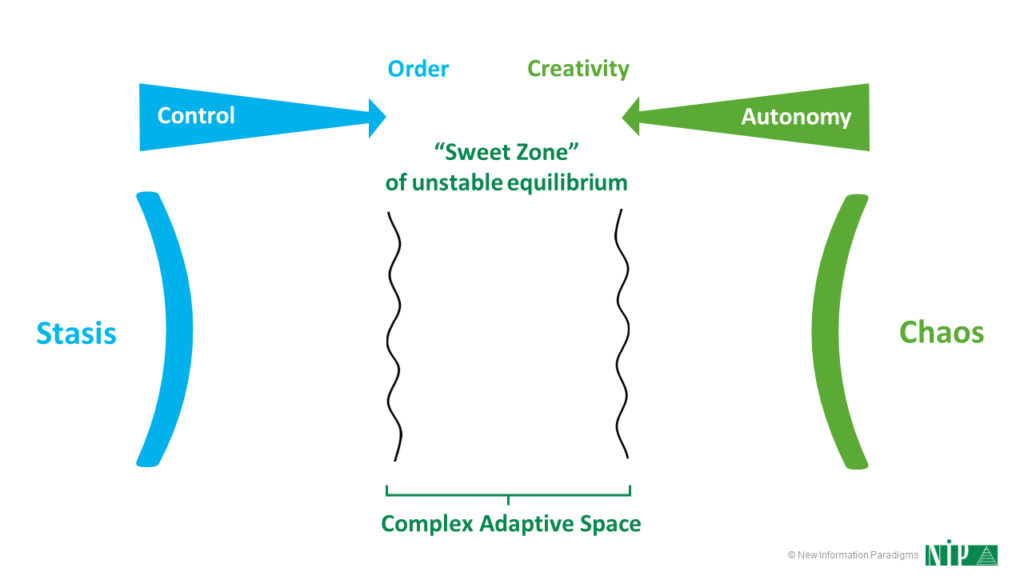

In between these two poles is a relatively narrow “Sweet Zone” of unstable equilibrium which somehow manages to both resist and utilize the pull of the two poles:

This is the zone of Complexity and complex adaptive systems, and whether we like it or not, this is where we almost always need to operate (the illusion of serene stability created by the Scientific Revolution has been shattered in all but the most tightly-defined and limited situations):

- Control mechanisms provide the Order necessary to define the left-hand boundary of the sweet zone and push “against” the opposing force of Autonomy (to resist the extreme of Chaos).

- Autonomy provides the scope for the Creativity needed to define the right-hand boundary and push “against” the opposing force of Control (to resist the extreme of Stasis).

The boundaries of this zone are then fuzzy because of the constant push-pull in these opposing directions – to both utilize the power of each pole and resist being pulled wholly toward it – and whilst this creates an equilibrium, it’s unstable because:

- This all leads to constant tension and dilemmas

- There’s always the risk of losing the delicate balance in the middle and lurching to one extreme.

The conceptual terrain for Value – as with all of reality – is therefore defined by (and between) polarity.

The Dynamics of Value

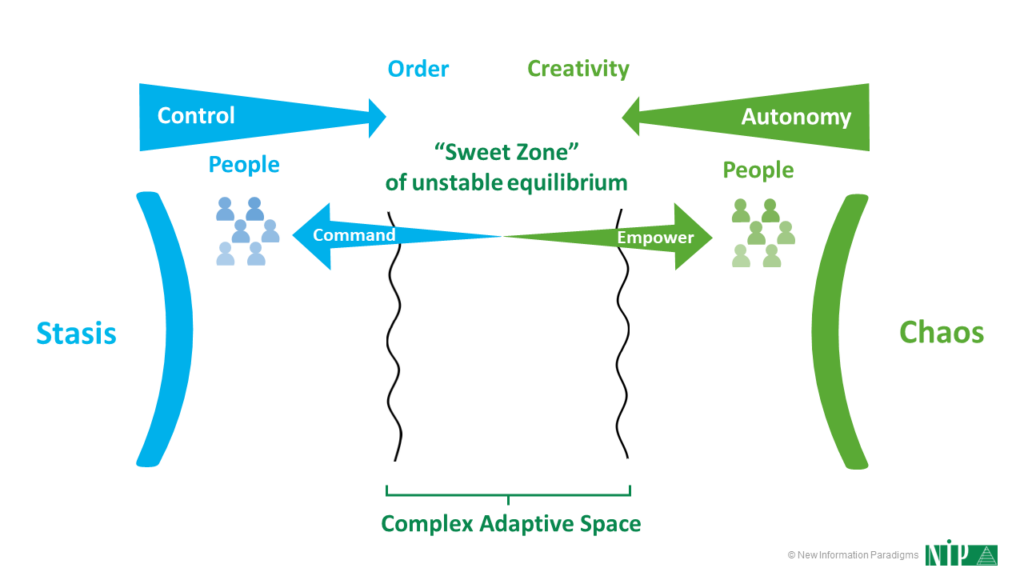

Let’s now start to ground this a bit by considering what happens with Value in this conceptual terrain – the dynamics of Value – and we’ll begin by introducing People into the mix.

After all, Complexity begins with People (every person is a living and breathing “complex adaptive system”!), and Value – the terrain we’re considering here – is of course ultimately defined and experienced by People:

When it comes to people, the tendency towards Stasis and Control is represented by Command; the tendency towards Chaos and Autonomy by Empower.

This means that – in the middle – these tendencies are again finely balanced: enough Empowerment to harness creativity and potential; enough Command given so that people have enough shape and structure to effectively channel their activity.

There’s a similar dynamic when we add in other resources, too:

The system has to Exploit existing resources to survive in the short term, but also to Explore new sources of resources to thrive in the future.

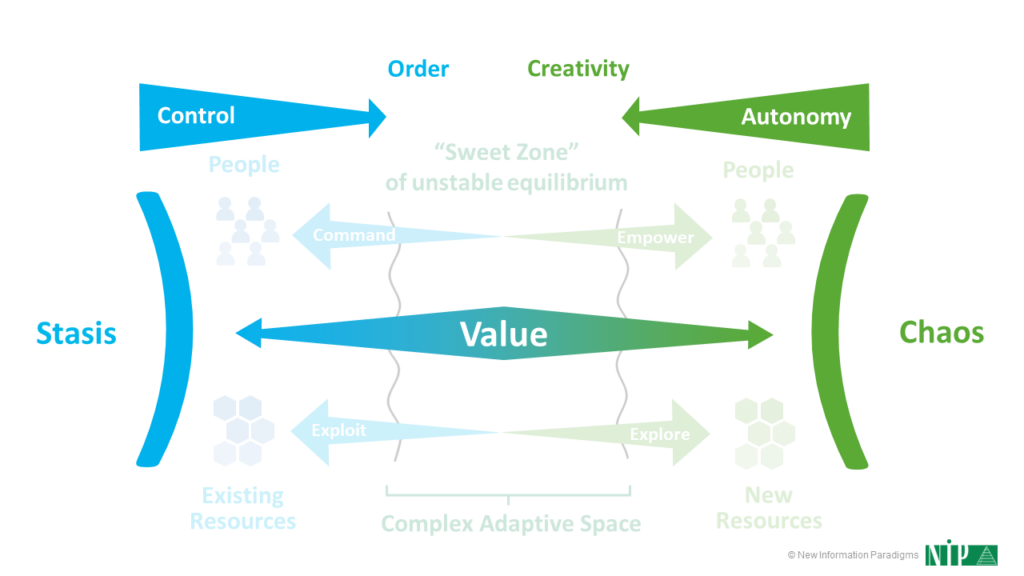

Now let’s concretely place Value in and over this terrain:

Value is therefore the underlying unifying and attracting force, underlying all the decisions needed about at what point and for how long to operate in Command/Exploit mode, and at what point and for how long to operate in Empower/Explore mode.

Value is therefore the tightrope underpinning a continuous dynamic balancing act to minimize waste whilst maximizing choice – agility in action, if you will.

Types of Value

But what can we say about what Value is?

Well, we’ve already said that Value is “ultimately defined and experienced by People” and that means – contrary to how Value is so often equated with price and cost (or how traditional economists reductively attempt to quantify it in “utils”) – it is primarily subjective.

This means we’re mostly in the realm of thought, perceptions, judgments and intangibles.

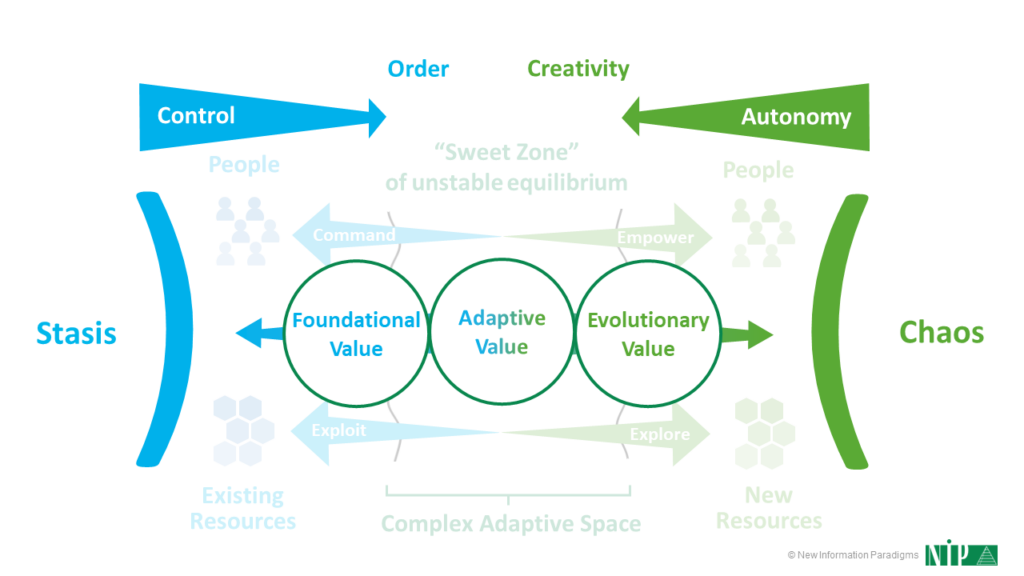

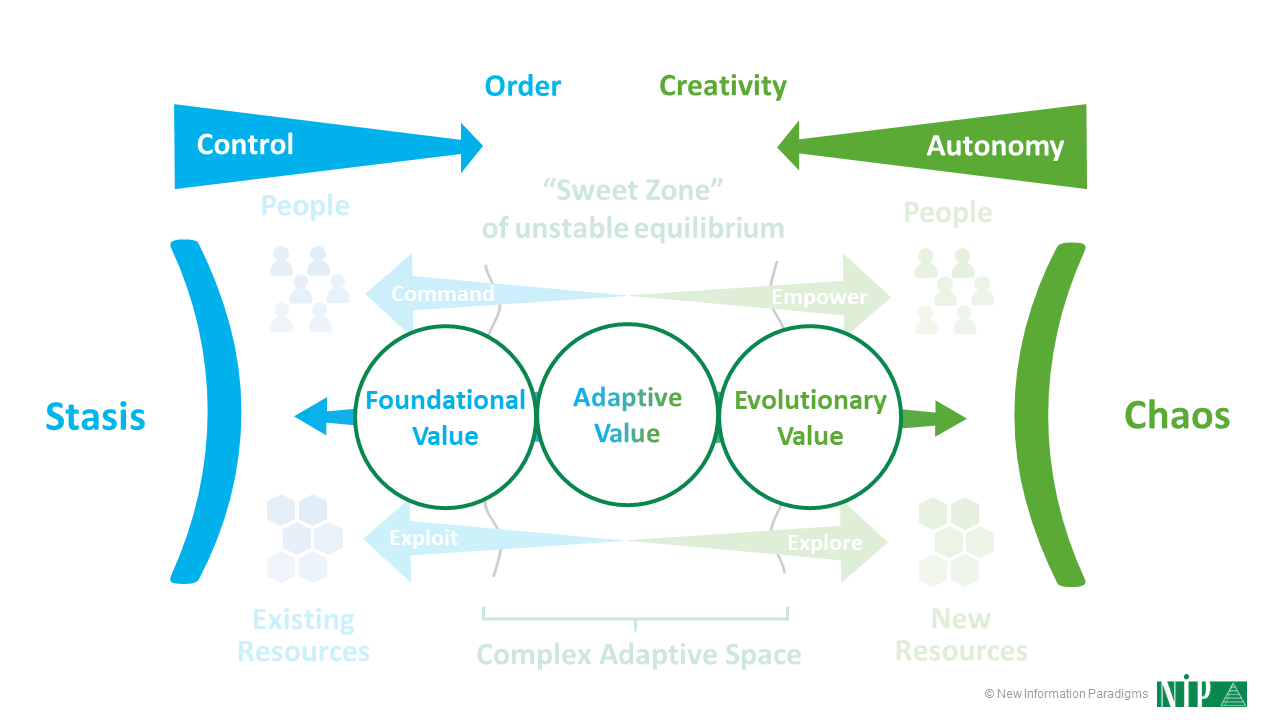

From here, the recently proposed physical Law of Increasing Functional Information seems to imply that there are three universal patterns or types of Value – each an important aspect of realizing Value – and these three types of subjective Value map neatly onto our polarity model:

- Foundational Value is towards the left-hand side of the sweet zone, encapsulated or embodied in replicable, reusable, ordered elements or modules: repeatability without change is the key, and because there’s no need to react to change, there’s scope to generate a surplus.

- Adaptive Value is in the middle of the sweet zone, where some of the surplus possible with Foundational Value is utilized to detect and respond to any gradual changes having an impact. The role of subjectivity is more obvious.

- Evolutionary Value is towards the right-hand side of the sweet zone, which is where the rate of external change is outpacing the current ability to adapt, requiring novelty to be actively sought and incorporated. The role of subjectivity is dominant.

In summary: Foundational Value is fixed and repeats success; Adaptive Value is a response to gradual change; Evolutionary Value is about getting ahead of change through innovation.

Subjectivity reigns supreme throughout the types of Value, and – regardless of the type of Value – the realization and management of that Value involves progress over time through a series of Desired States that exist between the Current State and Future State.

So what does Value Management mean in practice?

To begin with, it’s all built on the foundation of the human brain.

Value Management: the Brain as the Foundation

If this sounds in any way abstract, let’s remember what we said above: “…Complexity begins with People, and Value – the terrain we’re considering here – is of course ultimately defined and experienced by People“… together with “[Value] is primarily subjective. This means we’re mostly in the realm of thought, perceptions, judgments…”

…and what drives how people think, perceive, judge and act? The brain.

So how does the brain “work”?

Well, lots remains mysterious, but what is clear – especially from the work of Iain McGilchrist – is that the two hemispheres of our brain broadly work in very different but complementary ways:

Recognizing and utilizing the differences that make a difference between these ways of working is crucial – both hemispheres are equally important – but a major focus of McGilchrist’s work is how the “algorithmic” left brain is currently dominating thinking and discourse, at the expense of the “holistic” right brain.

We only need to consider the following to see the truth in this:

- Our innate general preference for order and regularity over “mess” and change.

- Our desire to master and control everything around us – significantly a legacy of the Scientific Revolution.

- How our organizations are almost always vertically structured, with hierarchies of responsibility and reporting, and separate departments or business units.

- Our obsession with quantification and numbers when it comes to what we measure and how we measure it (KPIs being the most obvious example).

When we look at the terms that define how the brain’s hemispheres work, though, we see the alignment with the poles in our value terrain:

- Stasis and Order: Left Hemisphere: “known”, “certainty”, “fixity”, etc.

- Chaos and Autonomy: Right Hemisphere: “new”, “possibility”, “flow”, etc.

This means that the left Brain maintains the left-hand boundary of the “Sweet Zone”, and the right brain maintains its right-hand boundary.

And so individuals all exist in a similar “Sweet Zone“, and so are subject to – and have to deal with – the same Command/Exploit vs Empower/Explore dynamic, with Value the underlying and unifying force between the poles of Order and Chaos.

Value Management: Things That Matter as the Framework

And what is Value when defined and experienced by People?

It’s the Things That Matter – anything and everything that is valuable to an individual (and by extension organizations and ecosystems, which are comprised of people) – and these function as the framework of Value and as a “shortcut” to it.

Why? Because:

- The Things That Matter are a proxy for Value – they represent it – so they quickly get to the heart of the matter, without having to define what Value is or isn’t (which we’ve done above, but which would be an analytical and theoretical “distraction” when needing to act).

- “Things That Matter” is a very common phrase that’s easily understood and acted upon – everyone has a view on the things that are important and relevant in particular situations and circumstances.

- It taps into fundamental neural pathways: since our earliest memories, we’ve been asked “what’s the matter?” and we know the power of asking that question when it comes to building empathy and understanding.

- Indeed, when we’re clear what matters to us, it’s then possible to step back and consider what matters to others..

Relentlessly focusing on the Things That Matter – surfacing, encapsulating and evaluating them – therefore acts as a “generative constraint”, balancing the need for order (constraint) and creativity (generative) and enabling the brain’s hemispheres to re-integrate with one another effectively.

But although the Things That Matter are therefore the framework and beating heart of Value Realization and Value Management, they still need to be operationalized, so that they can be embedded, spread and scaled.

Value Realization: Value Codes as the Means

This operationalization is what our Three Step Process achieves, but perhaps the pivotal step – the one that truly “unlocks” the Things That Matter – is the second step, that of Value Coding.

This is where the typically high-level and subjective Things That Matter are re-expressed as Value Code measures that introduce specificity and objectivity to enable the management and progression of intangibles: the means of Value Management.

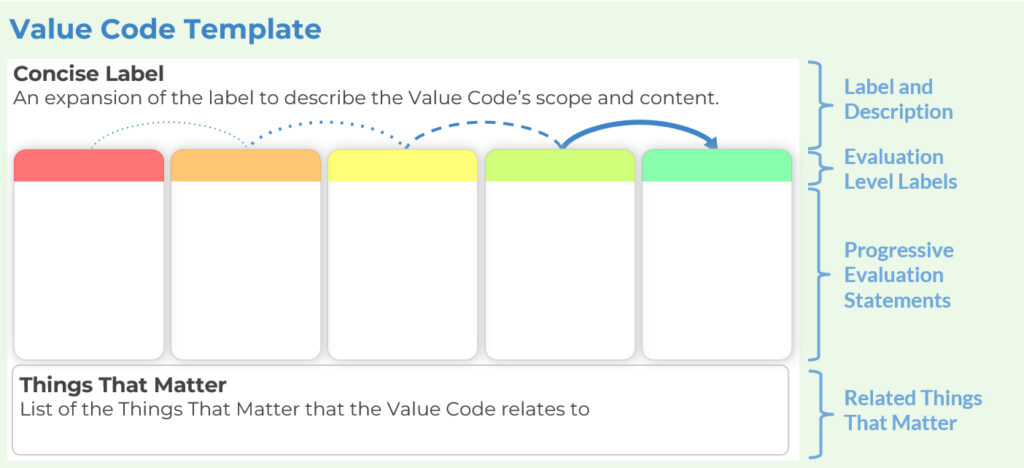

Here’s our Value Code template:

Each Value Code has a Label, and a Description, followed by a set or table of Evaluation Level Labels each with associated Evaluation Statements.

Typically, the statements express five progressively more challenging potential states, so for example, the range might be from “Failing” through to “Best Practice”: the more detailed and situation-specific the statements are (and the more involved the users are in the creation process) the better.

After all, users know what reflects best practice (and what KPIs or OKRs) should be incorporated to differentiate between the evaluation statements – in other words, they know the differences that make a difference to performance.

(To understand the Value Coding process in more depth, my colleague, Stephen Bruce, has written up a worked example of developing Value Codes from Things That Matter.)

As for why the development and evaluation of Value Codes works, we’re back to our brains and how they’re harnessed:

- The left-brain relates to the list, structure and “formality” of Value Codes, as well as the scope to attribute and capture numerical evaluation scores.

- The right-brain relishes the opportunity to explore the big picture and come up with creative solutions to close gaps between evaluation statements that represent a current state of dissatisfaction or unease, and those representing a more desirable future state.

- This harmonization contributes to a greater sense of well-being and purpose, which creates a virtuous circle of engagement, motivation and change.

Now, the set of Value Codes will shift and change over time – some will drop out and some will come in according to changing circumstances – and some will expand out to potentially create a more detailed taxonomy (e.g. a generic “Security” Value Code may be factored out into “Cyber Security” and “Site Security“).

But the Value Codes – and the Things That Matter they relate to – therefore fully map the Value terrain at any one time (in both breadth and depth), and also over time; as part of this, they also support each of the three “types” of Value we saw above:

- Foundational Value is expressed through the selected set of Value Codes, specifically in the form of their structure and content.

- Adaptive Value comes out of the review process itself– has anything changed? Do we need to react?

- Evolutionary Value emerges when individuals and teams creatively recognize an opportunity for a completely new Value Code or for an innovative way to progress to a higher evaluation score or statement.

On which note, once a set of Value Codes is in place, it’s possible to consciously choose and keep a record of where and how limited resources have been allocated and moved across the set. This directly links results to choices made and creates a rapid and immediate feedback loop that can capture what works (and doesn’t) to embed, spread and scale it.

In Conclusion

So, we have a way to measure – or evaluate – Value that works with and has emerged from the most fundamental nature of reality and of how we operate.

Whilst we’ve set out this deep theoretical grounding, we’ve shown how it engages people naturally without the need for any of that background, and how the Things That Matter and Value Codes organically and holistically address the whole Value domain in all its dimensions – including over time.

This is how Value Management works. This is why Value Management works.

But given that we’ve made the case that perceiving, valuing and creating all ultimately takes place through – and in – the human brain, I’ll end with what Iain McGilchrist has to say about the two hemispheres:

In the left hemisphere, the world is simplified in the service of manipulation: it is made of isolated, static ‘things’ – things that are already known, familiar, predetermined and fixed. They are fragments, that are devoid of context, disembodied and meaningless – abstract, generic in nature, quantifiable, fungible, mechanical and lifeless. This is a world that is reconstructed after the fact: literally two-dimensional, schematic, theoretical. Here, the future is a fantasy that remains under our control, so the left hemisphere is unreasonably optimistic and fails to see the dangers that loom.

In the right hemisphere, by contrast, there is a world of flowing processes, not isolated things; one where nothing is simply fixed or entirely certain, exhaustively known or fully predictable, but always changing, and ultimately interconnected with everything else. A world where context is everything; where what exists are wholes, where what really matters is implicit; a world of uniqueness – one where quality is more important than quantity – a world that is essentially animate. Here the future is a product of realism, not denial. This is a world that is fully present, rich and complex, a world of experience, which calls for understanding. The right hemisphere is more cautious, and in general more realistic.

“A Revolution in Thought? How hemisphere theory helps us understand the metacrisis”, Darwin College Lecture delivered in Cambridge, 9 February 2024