What Value Is: Part 3 – Understandable, manageable and measurable

- Part 1: Value is misunderstood

- Part 2: Value is not properly in focus

- Part 3: Value is understandable, manageable and measurable

“Value”. One of the most frequently-used words in commercial contexts, and we think we all know what it means. But what is “value”, really? Do we understand it? And, if we don’t, what goes wrong? In this series, we’ll show what value really is and, ultimately, why it’s all that matters.

In this third and final part, we show how Value can be significantly understood and, from there, how it can be managed and measured – creating a huge opportunity.

Last time, we saw how – despite being all that ultimately matters – Value isn’t properly in focus.

We saw how our organizations lose touch with it, and how this reflects imbalances and biases in how we think, in our relationships and in how we work.

And we finished by asking how we can “demystify” Value – especially subjective Value, which increasingly dominates – and from there how to manage and measure it.

The good news is that there is a way forward, and it begins with how subjective Value is significantly understandable.

Value is significantly understandable

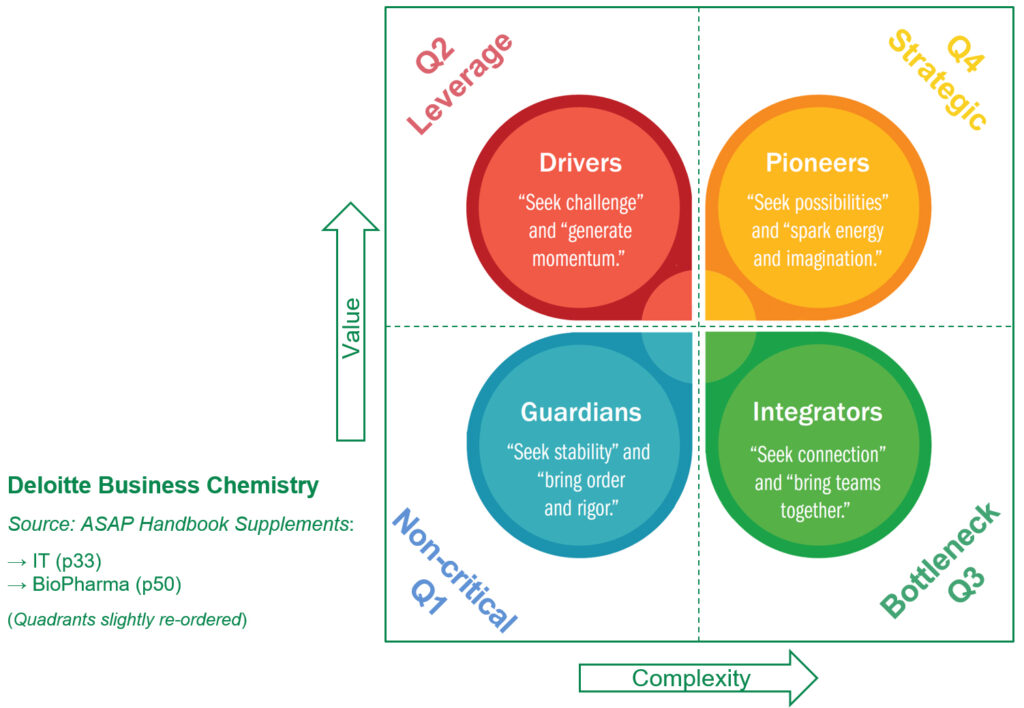

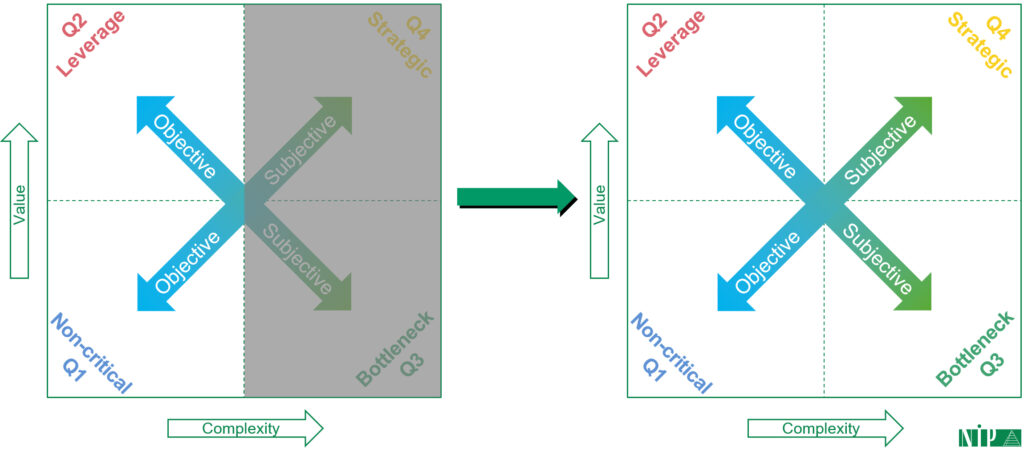

To start explaining this, we return to our Kraljic matrix from Part 2, because this already indicates that we recognize consistent patterns in Value, and especially that quadrants are a really powerful tool here.

Indeed, having looked-at and synthesized many high-level schemas of personal values, personality types, organizational drivers and cultures, a pretty much universal 2×2 matrix approach emerges, and we’ll include one from Deloitte:

(This version comes from our friends at the Association of Strategic Alliance Professionals.)

Whilst it’s talking about personality types, it maps neatly onto the Kraljic matrix, even if the blue and green quadrants might initially seem less obvious:

- Q1 relationships are “non-critical” in significant part because “Guardians” have brought stability, order and rigor.

- Q3 “bottlenecks” are of course absolutely what “Integrators” seek to resolve.

So this mapping starts to indicate that there’s a universal structure here – one that works equally well for individuals and organizations – and, with that in mind, we then relabelled the quadrants to reflect their main focus or priority:

Again, with “Bottleneck”, it’s “People” that are usually at the root of the bottlenecks that integrators look to resolve; with “Methods” for “Non-critical”, these bring the stability, order and rigor here.

These new labels then also make clear that each of the quadrants is equally important (“Non-critical” otherwise potentially sounding unimportant!).

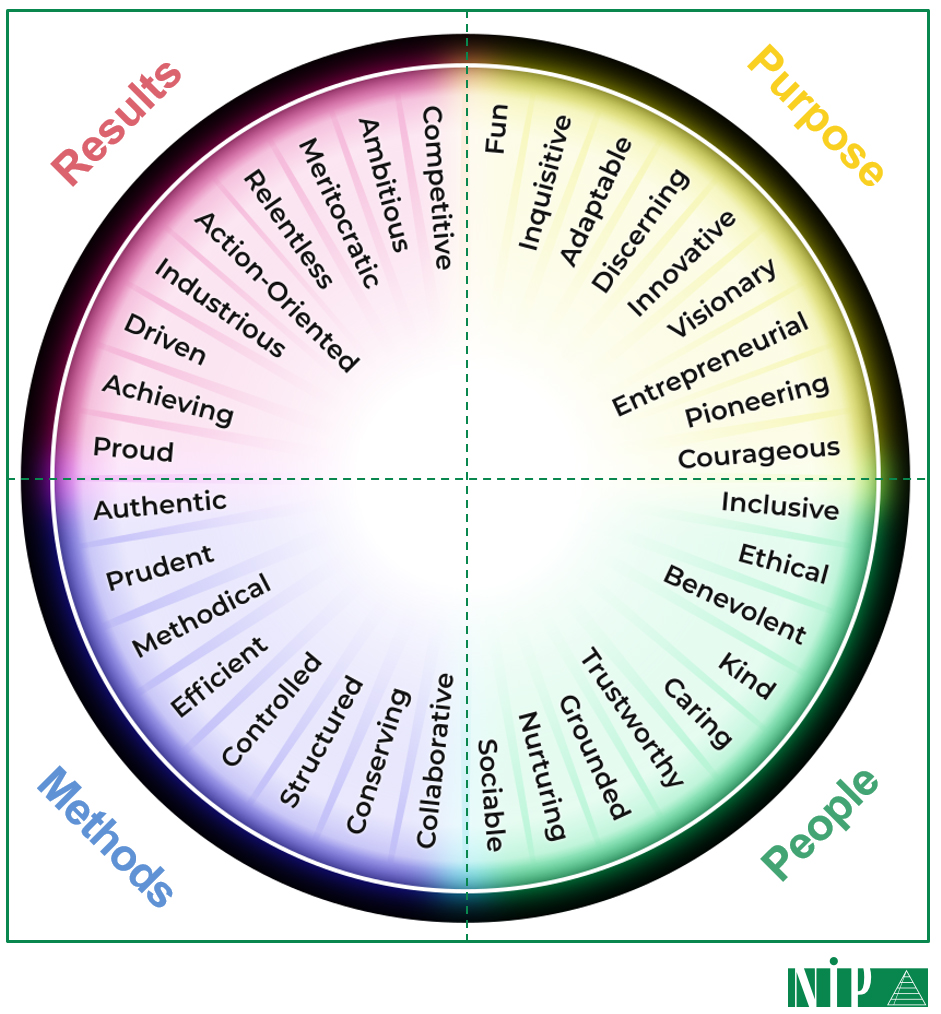

We then went further, and fleshed out each quadrant’s distinct and specific Values:

Have a real look at this wheel. Have you ever thought about your organization like this? Or your customer?

The Values then flow into each other in both directions, e.g. “Visionary” in the top right naturally leads to, or reflects, being “Entrepreneurial”, and then onto “Pioneering”, and so on; it also works the other way round, too (“Visionary” naturally leading to, or flowing from, “Innovative”, and so on).

Now, of course, these are only single words, but we’ve also expanded each of the Values into more detail behind the scenes, so we can get pretty precise, and this structure can then help us in several ways.

How a structure of Values helps us

The first way that this structure of Values helps us is that it makes clearer why focusing exclusively on capability, best practice, and so on – “Methods” – is so limited:

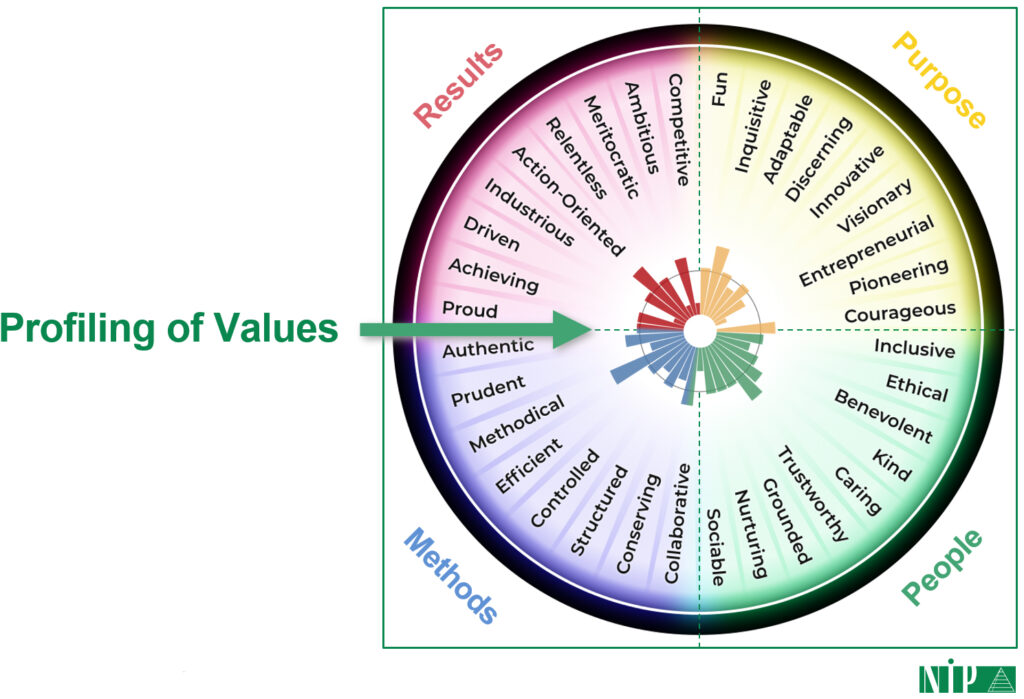

Second, we can do profiling of Values: what customers value; what we as organizations and as individuals value; what our partners value; what shapes that continuous and changing process of valuing – Value as a verb from Part 1:

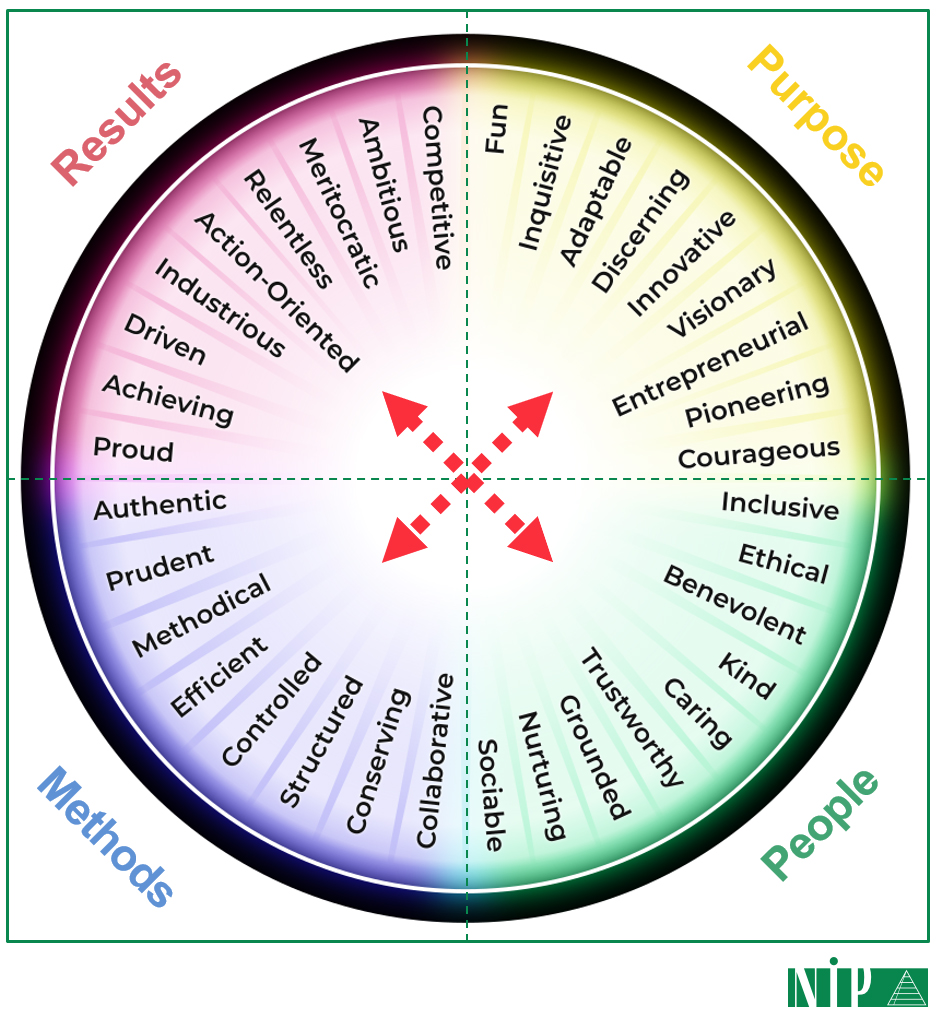

We can identify alignment and fit, or mismatches, with our customers or our partners – in particular that there are often tensions (or even clashes) between opposite Values and quadrants.

Now some of these opposites and clashes are less immediately obvious – you’d need the full detail of each value to see that, but in general, red might see green as wasting time, whilst yellow might see blue as needlessly bureaucratic, and so on:

But if these differences are understood, they can then be managed, and even used to advantage – including making any tensions there sources of creativity, rather than of difficulty.

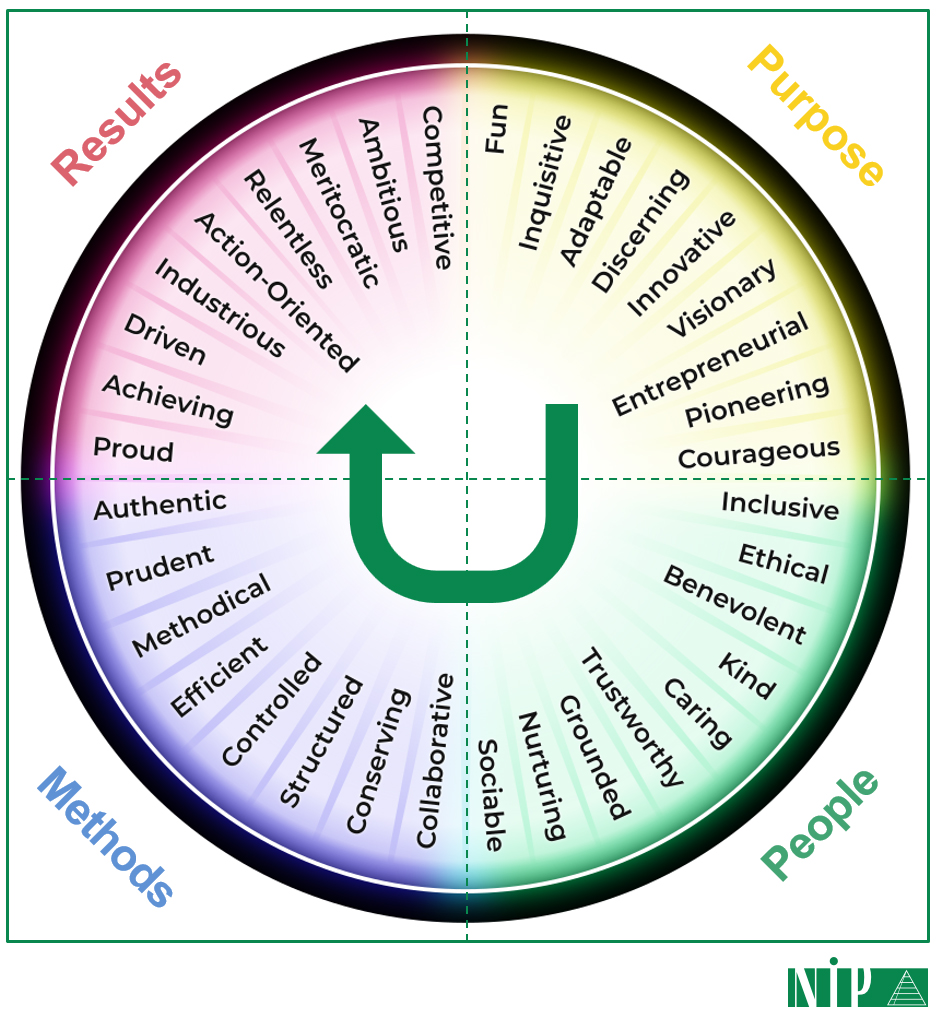

And finally, lifecycles can also be tracked.

Now there’s a lot more detail here, but a new product, for example, likely starts in the yellow quadrant, enters an initial take-to-market phase in the green quadrant, before being operationalized (blue) to yield market results (red):

So this structure helps to map, track and often plan for change in Value.

But to do these things, we’re going to need a way of managing and measuring Value.

Things That Matter

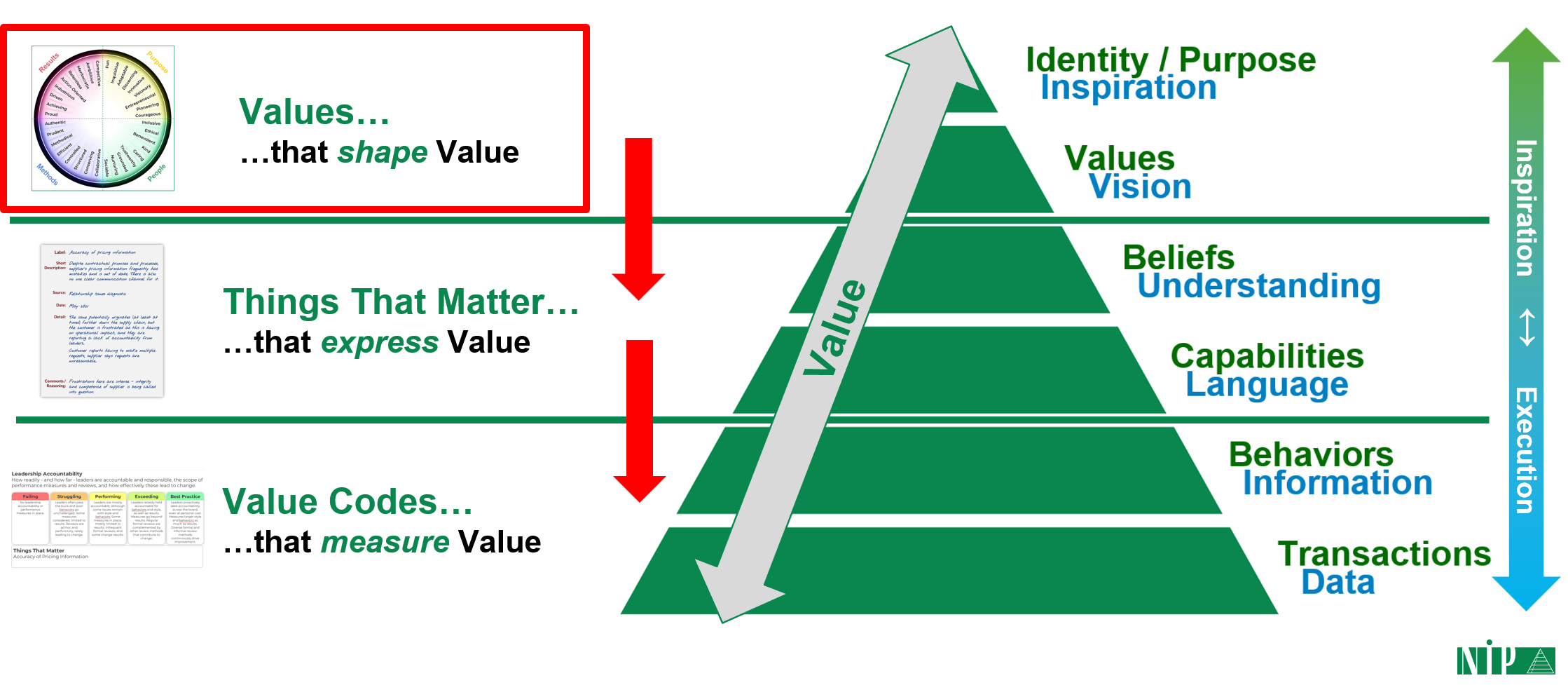

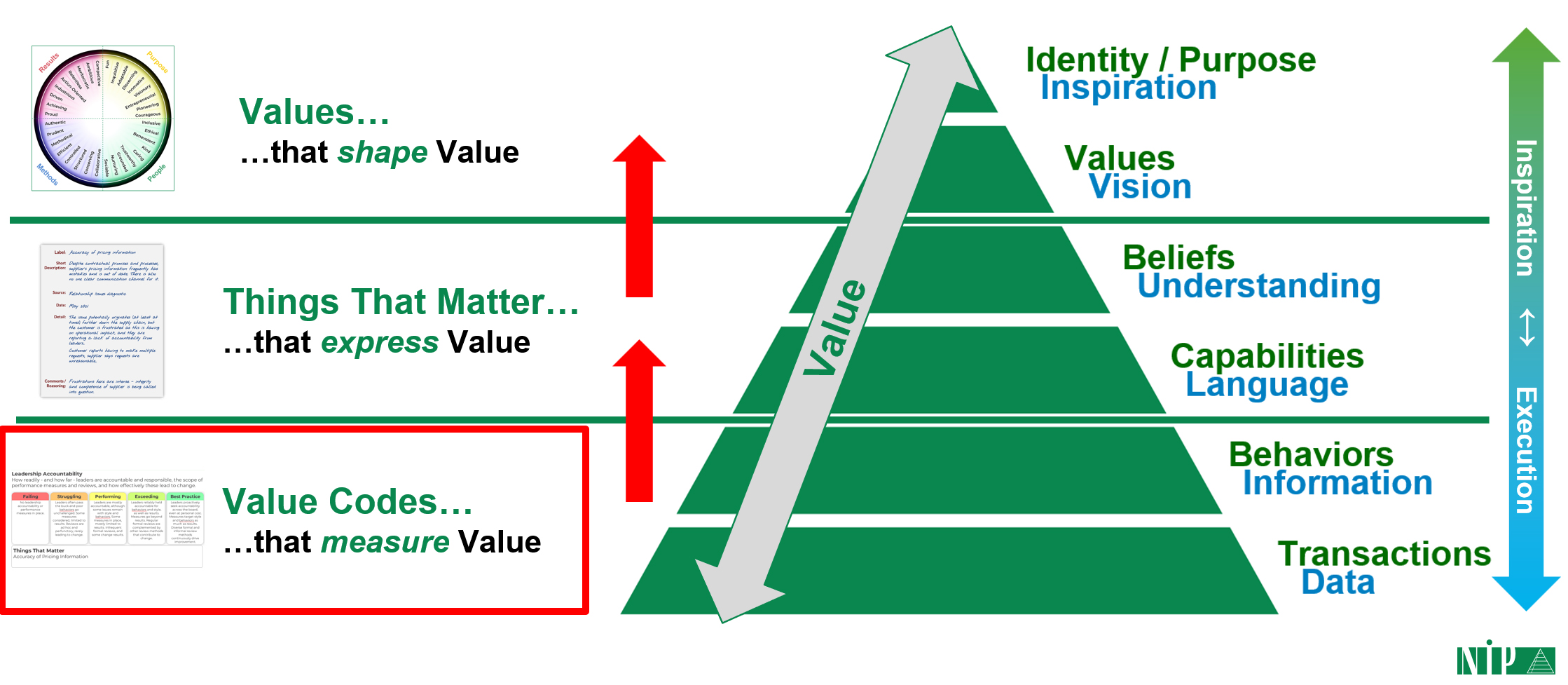

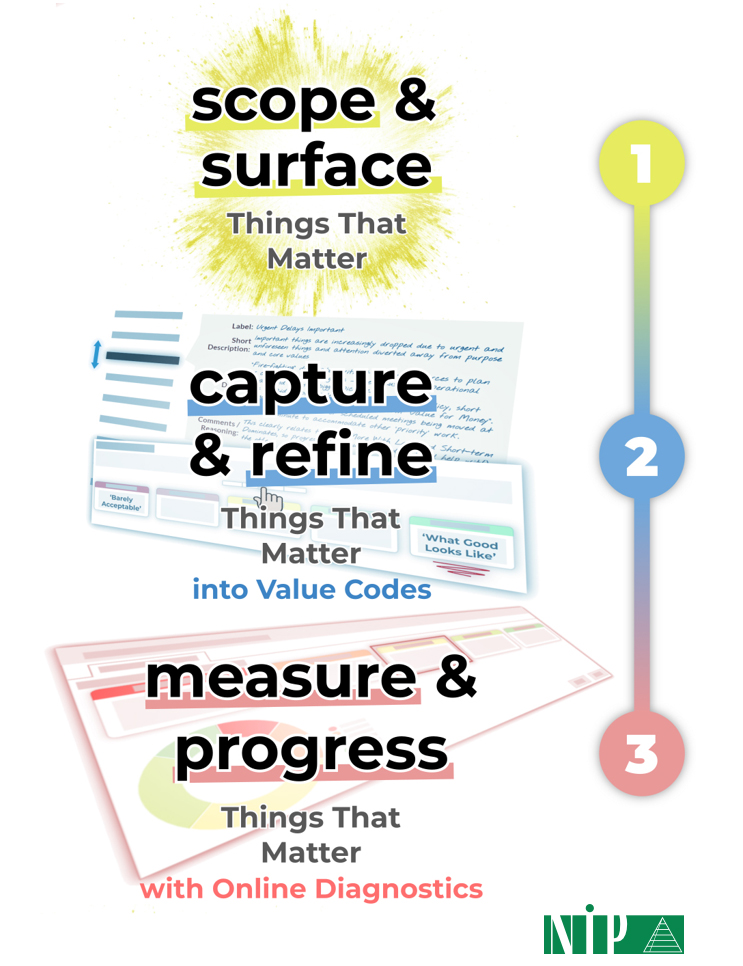

We see the managing and measuring of Value as a three step process:

And this begins with scoping and surfacing the Things That Matter – the specific and recognizable components, or elements, of Value.

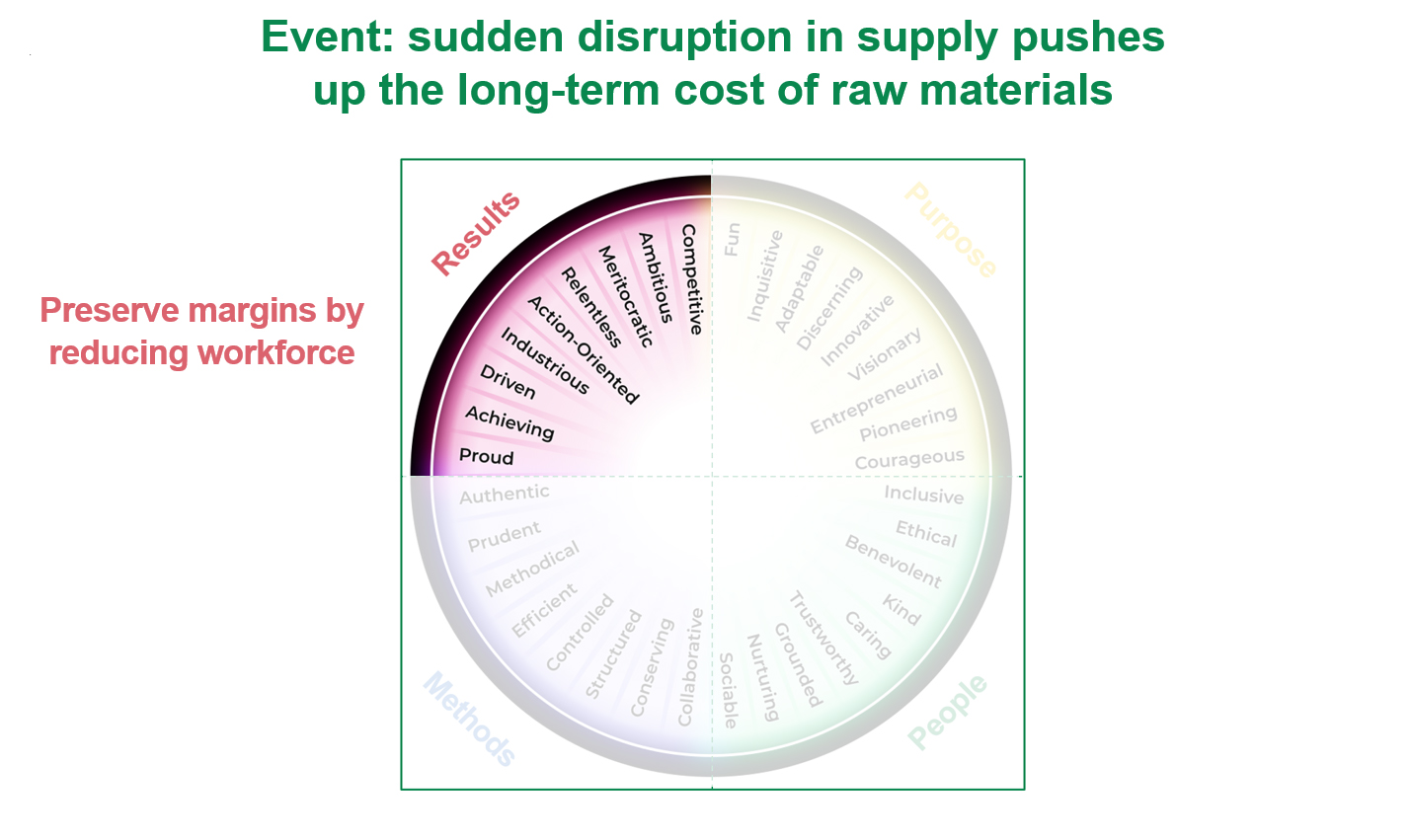

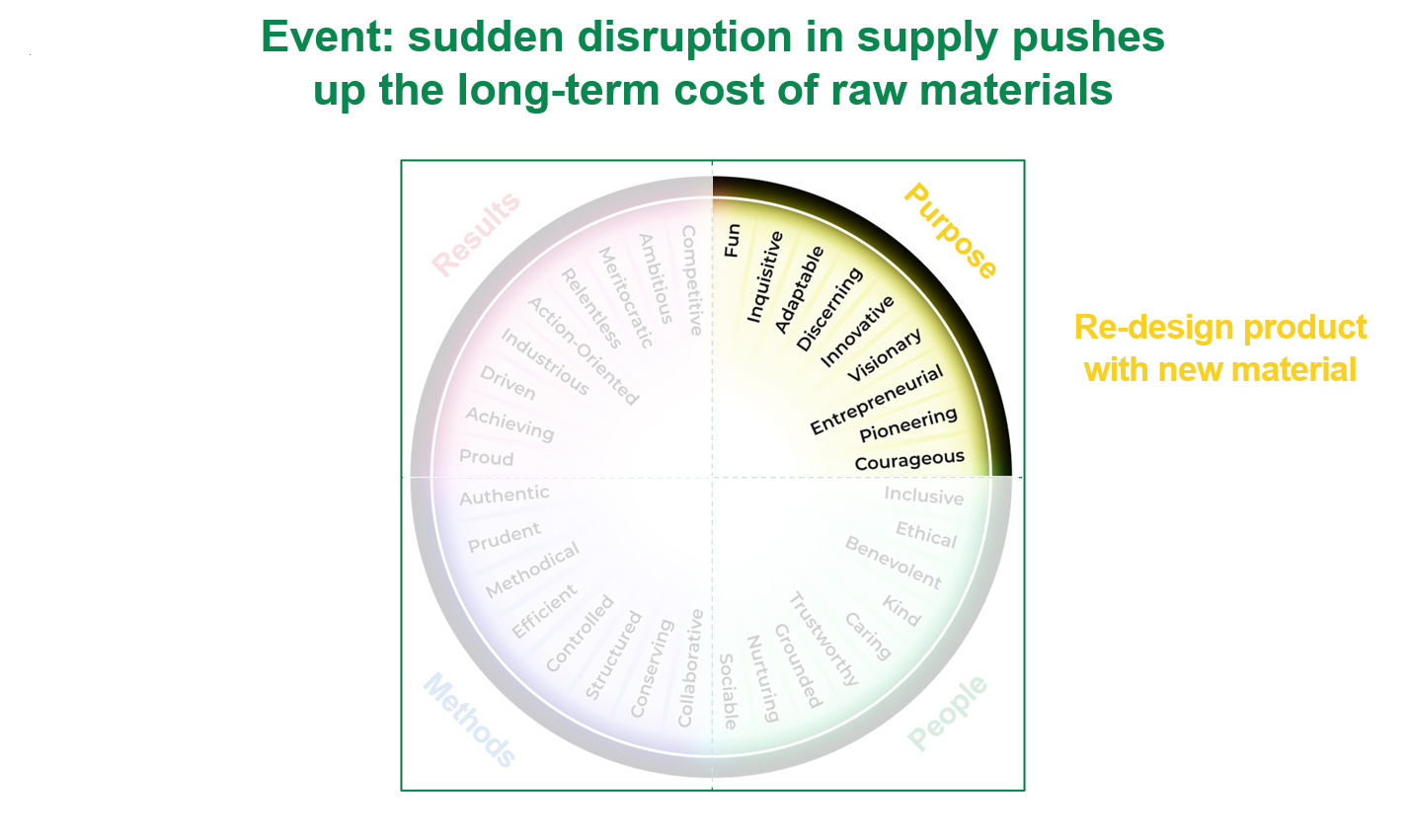

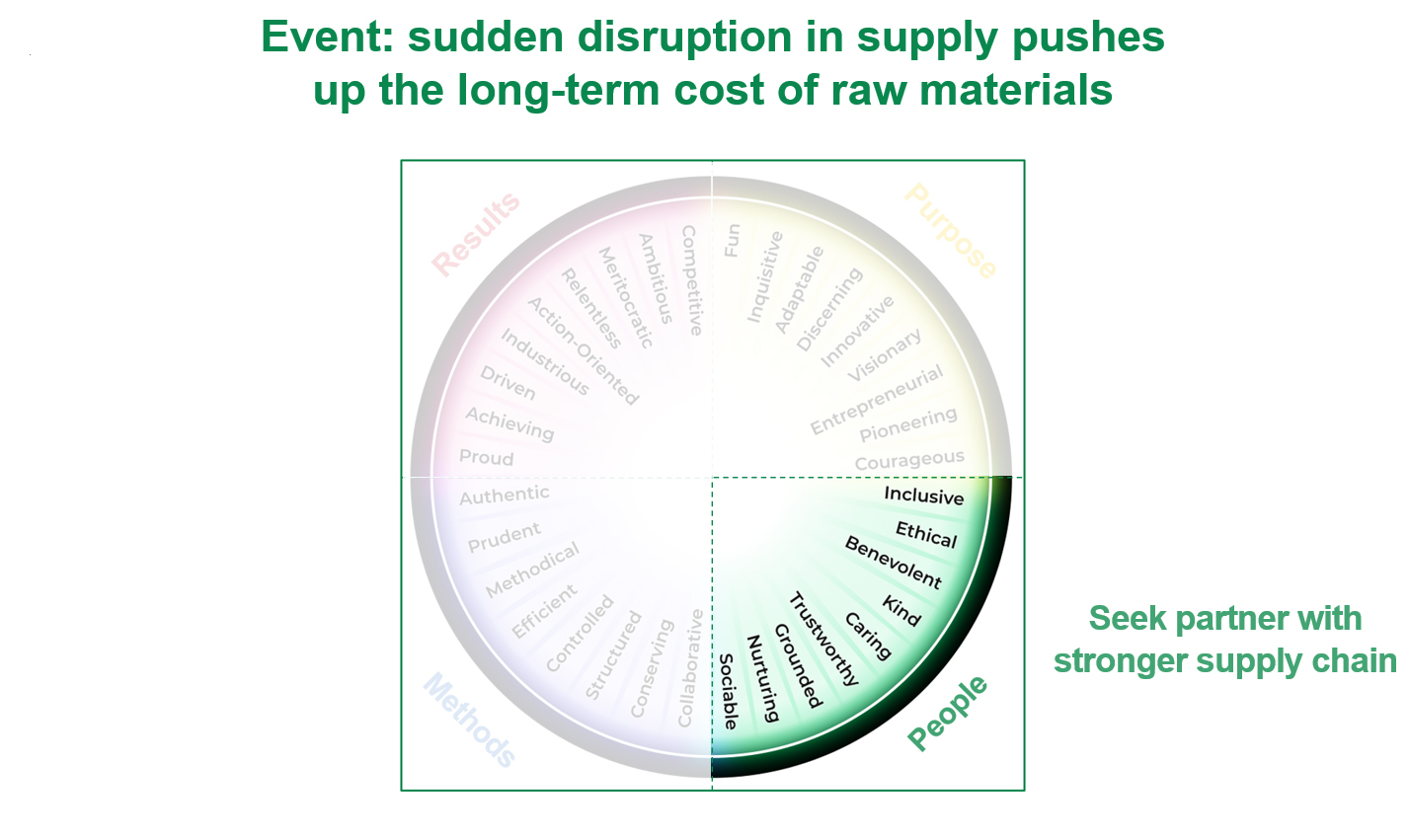

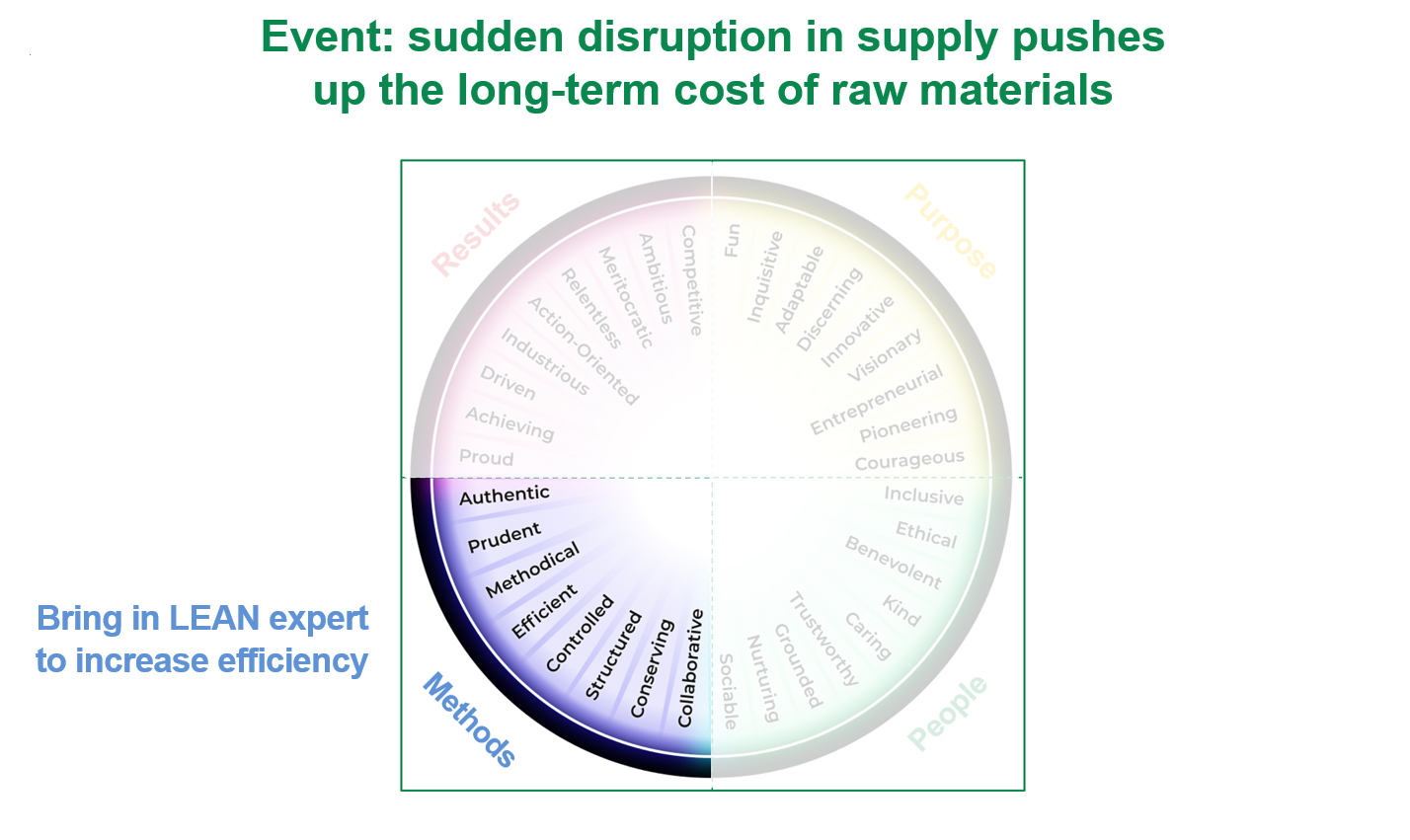

These are the tangible expressions of the underlying Values we’ve just seen, now applied to the situation and to events, and to make this point clearer, imagine that there’s a sudden disruption in supply that pushes up the long-term cost of raw materials.

What then matters as a result will vary hugely based on the underlying Values:

Where results (top left) are the main focus, the priority will likely be to preserve margins, even if that means reducing the workforce.

Or, moving clockwise, in a more innovative and purpose-driven context, the product might be redesigned around a new, alternative material.

In a more people-centered environment, the workforce likely comes ahead of margins: it might be time to partner with an organization with a stronger supply chain (the opposite response to the red quadrant).

And finally, where methods are the focus, you might look to improve efficiency by implementing LEAN (the opposite response to the yellow quadrant).

It’s a crude example, but it makes the point: underlying Values shape the Things That Matter: first and foremost, your customer’s Values (which shape their Things That Matter), which your organization then responds to with its Things That Matter (shaped by your Values), and so on down the value chain.

That interplay no doubt sounds complex, and it usually is (it’s that interconnectivity and interaction that’s fundamental to Complexity, as we saw in Part 1)…

…but talking in terms of Things That Matter helps sidestep and begin cutting through all that, because it starts to express what “Value” means in practice.

Why Things That Matter “work”

These examples make clear that Things That Matter occupy that crucial middle ground between abstract and actionable (something we’ll come back to shortly).

They’re recognizably about something in practice, but they’re also not immediately “doable”.

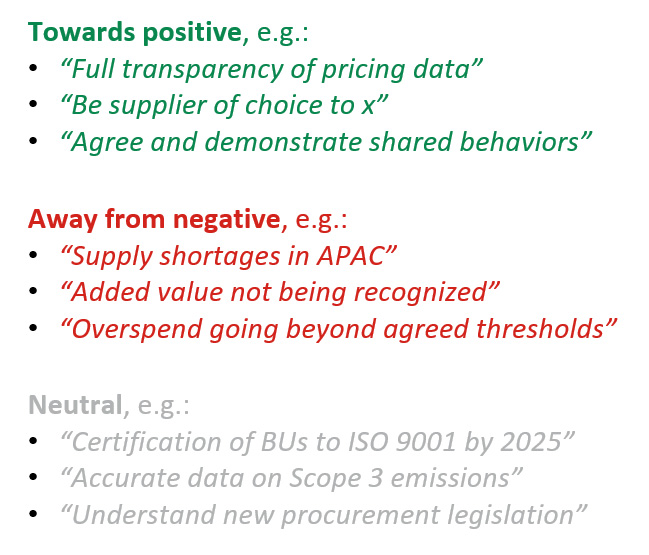

They also nearly all involve subjectivity, as reflected in their different outlooks: towards-the-positive, away-from-the negative, and more “neutral” in the middle.

That subjectivity is then a big reason why Things That Matter are largely situation-specific: yes, there are recurring patterns and similarities, but you can’t assume that they’re the same in each situation.

There are three reasons why all this is so powerful…

First, surfacing and expressing the “Things That Matter” is simple, intuitive and engaging.

Ever since childhood, we’ve been asked “what’s the matter” as the way to “get out” what’s important, and it’s an entirely open phrase, so whatever comes up, it will be unfiltered and relevant.

Second, the “Things That Matter” are a “bridge” between “Value” as a noun and “Value” as a verb (again see Part 1 on this): “Value” as a noun is represented by the word “things”, but the “matter” part of the phrase harnesses the active valuing verb form.

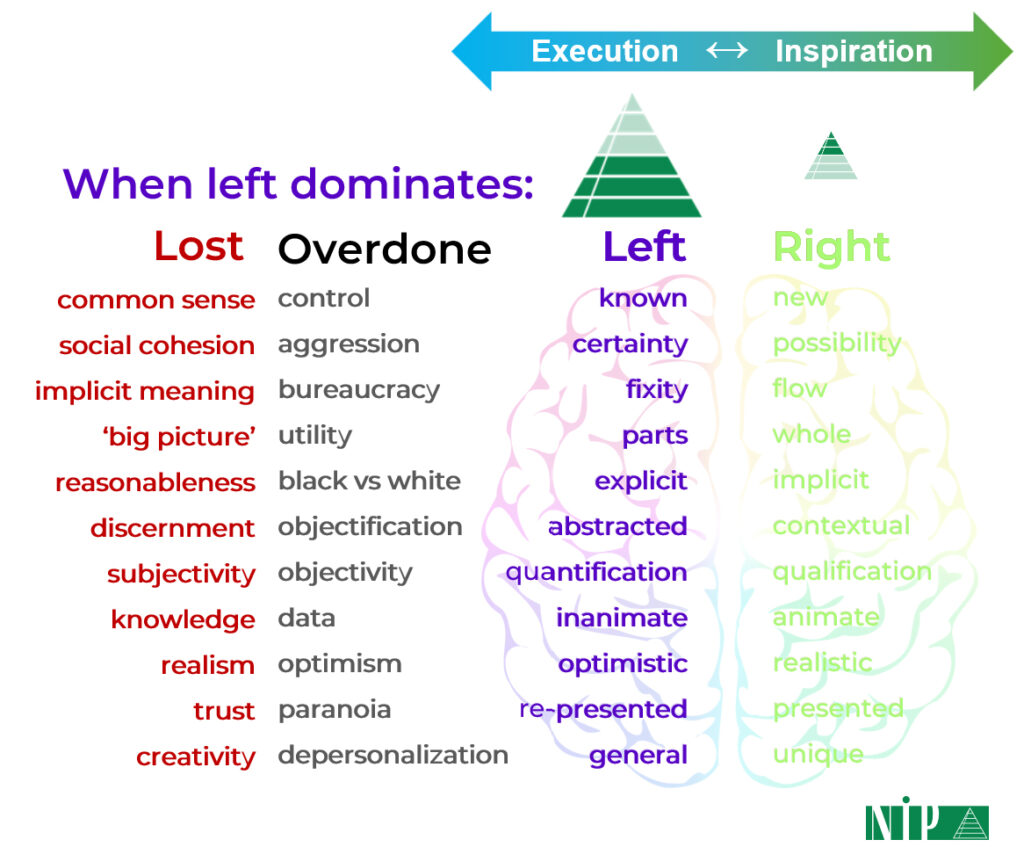

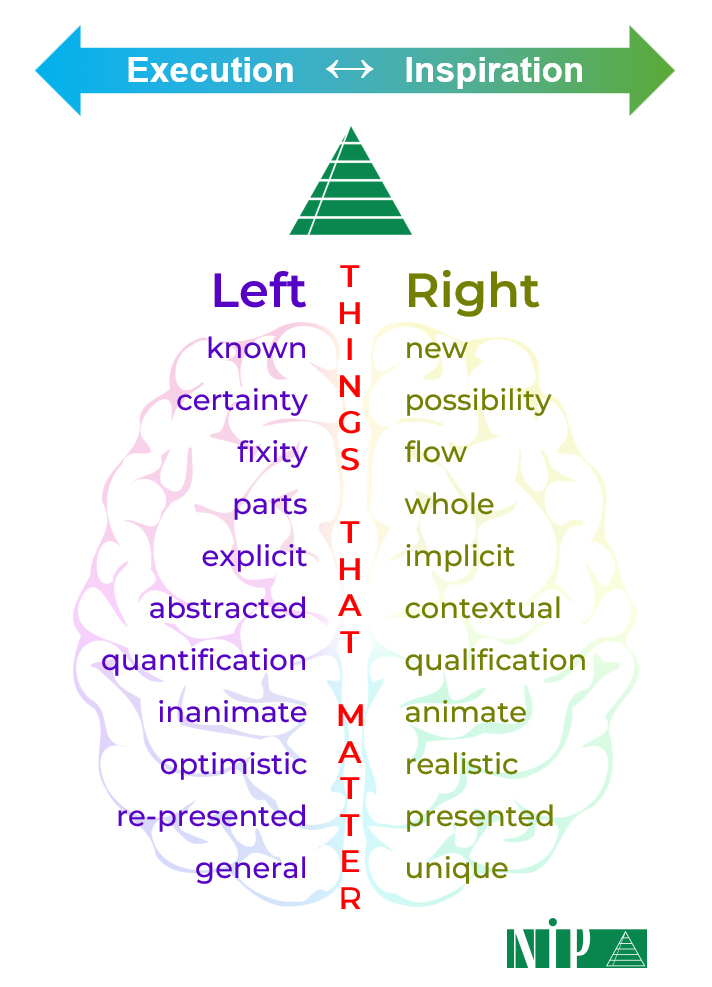

And finally, the Things That Matter therefore rebalance how we think.

So, back to our brain diagram from Part 2, and with the Things That Matter being between abstract and actionable:

“Abstract” (verb) maps perfectly to the big-picture right hemisphere; “actionable” (noun) to the execution-focused left hemisphere. The Things That Matter therefore sit between the hemispheres, and this restores balance and helps to get the best out of both:

So, surfacing what matters is crucial: it’s the beginning of clarity and of empathy.

But it’s also not enough, you need to be able to do something about it.

From Things That Matter to Value Codes

This all begins with properly capturing those Things That Matter, not least to share what you’ve surfaced, and here’s an example of one that’s been fully written-up:

The main thing to note, though, is that a full write-up like this helps you spot the distinct specific and discrete topics covered, and these will then be our Value Codes – what make Things That Matter measurable.

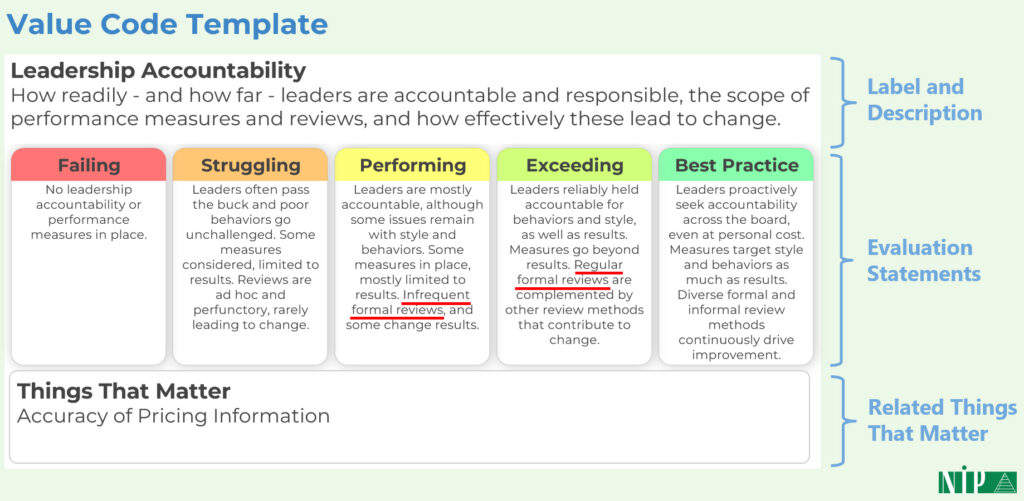

Like the Things That Matter, Value Codes also have a consistent format, and our primary focus for now is the evaluation statements in the middle:

These statements objectively ground what this aspect of the Thing That Matters looks like in practice (which is why they’re ideally developed, or at least refined, by front-line participants); they show the progression towards what good looks like, with the differences between them helping map how to get there.

So, in this example, if it’s at a state of “Performing”, formal reviews are infrequent; however, for “Exceeding”, they’ve become “Regular”:

In other words, potential improvement actions are embedded, and when Value Codes are then evaluated by the people involved, they also reveal perception gaps because. whilst the statements are mostly objective, there will absolutely be varying experiences around them.

But then, you can reach an agreed consensus on where things are at, set a target, and decide what to do – including with what priority.

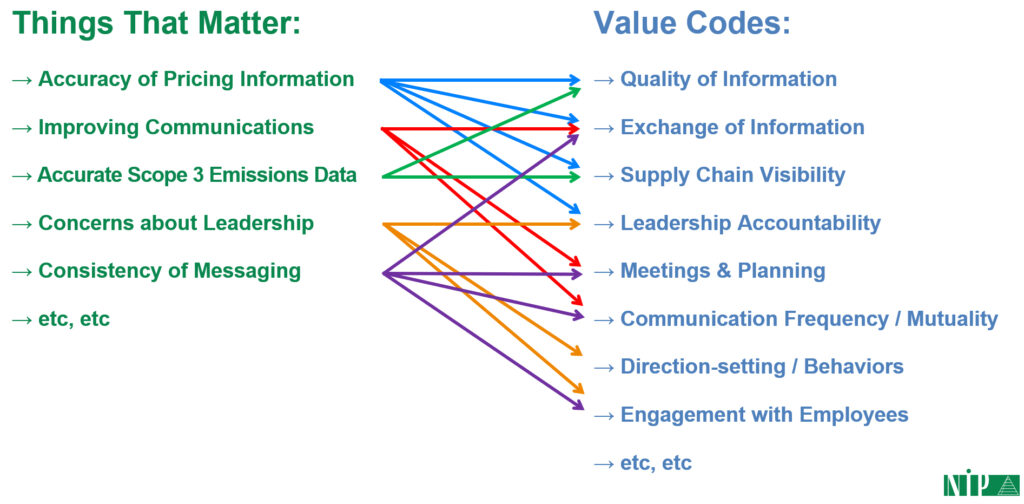

If we then add in some more example Things That Matter and their linked Value Codes, we then see how a “network” builds-up:

On the left are high-level, primarily subjective Things That Matter; on the right, these have now been distilled down into a set of specific, discrete and primarily objective Value Codes that can be measured, managed and progressed.

So, we’ve dealt with the challenges around subjective Value that we set out above: we’ve “demystified” it, and made it measurable and actionable.

And that means we can widen the effectiveness of relationship management in our most crucial Q3 and Q4 relationships, where subjectivity dominates:

We now have a complete Value framework.

A complete Value framework

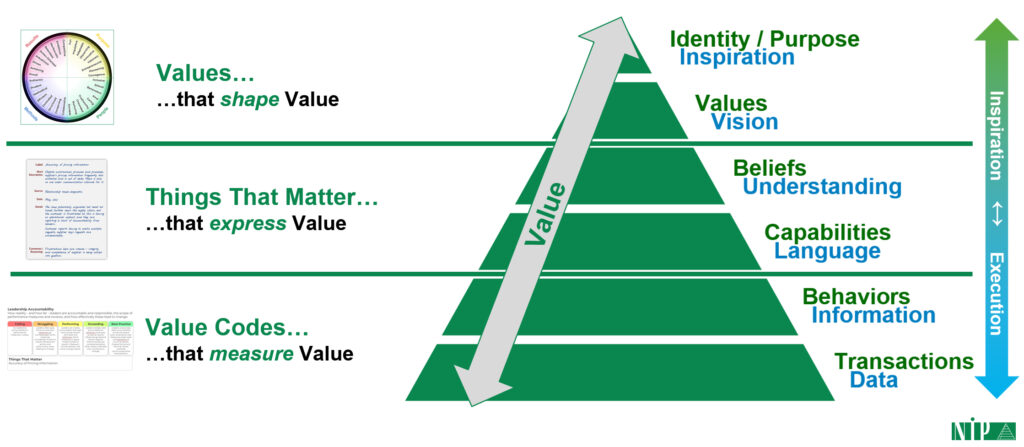

The framework consists of three “layers”:

- The structure of Values that are constantly shaping Value

- The Things That Matter, which express those Values in context

- Value Codes, which make Value measurable and actionable

And you can enter-in to this framework at any point:

- You could start with underlying Values and, from there, the Things That Matter they drive, and ultimately their Value Codes

- Or, you could start with the Things That Matter, and then move either “up”, “down” or both

- Or you could work “up” from what emerge as priorities from Value Codes, perhaps Value Codes reworked from best practice or standards (i.e. recognizing that they express potential Things That Matter, but beginning to harness them more effectively)

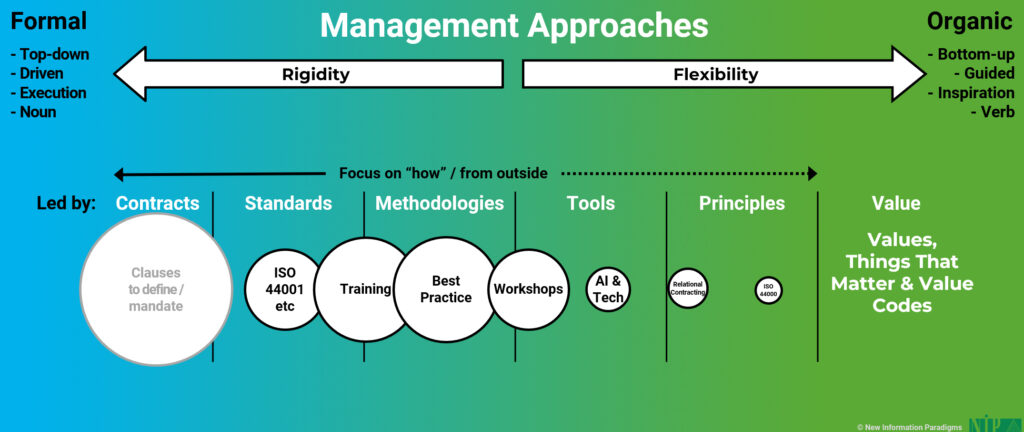

Wherever you start, though, it’s this framework of Values, the Things That Matter and Value Codes that fills the gap in how we’re currently working:

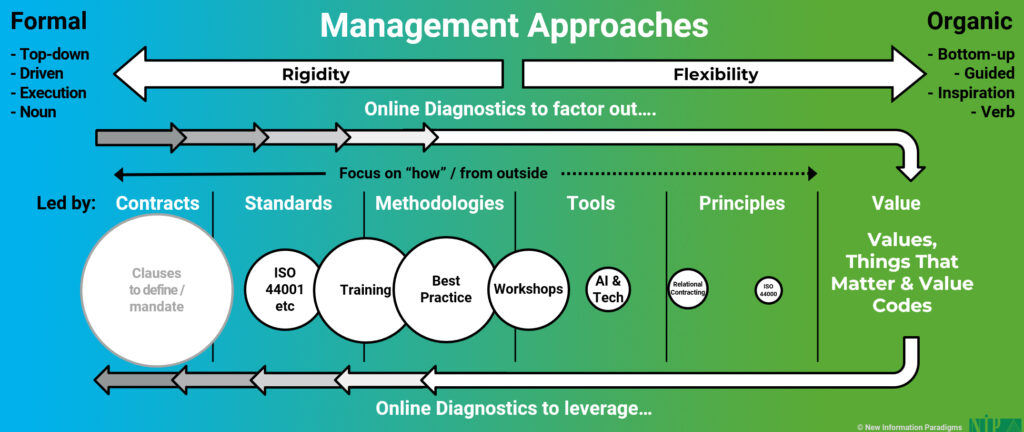

But how do you deliver all this? With online Diagnostics.

Online Diagnostics

Online Diagnostics firstly help factor out and continuously stay on top of Values, the Things That Matter, and Value Codes, and they secondly harness this clarity to really leverage the other approaches:

After all, with our limited time and resources, we’re now fully guided as to which tools and approaches – even which specific parts of them – are most appropriate and relevant, and when.

But why online Diagnostics?

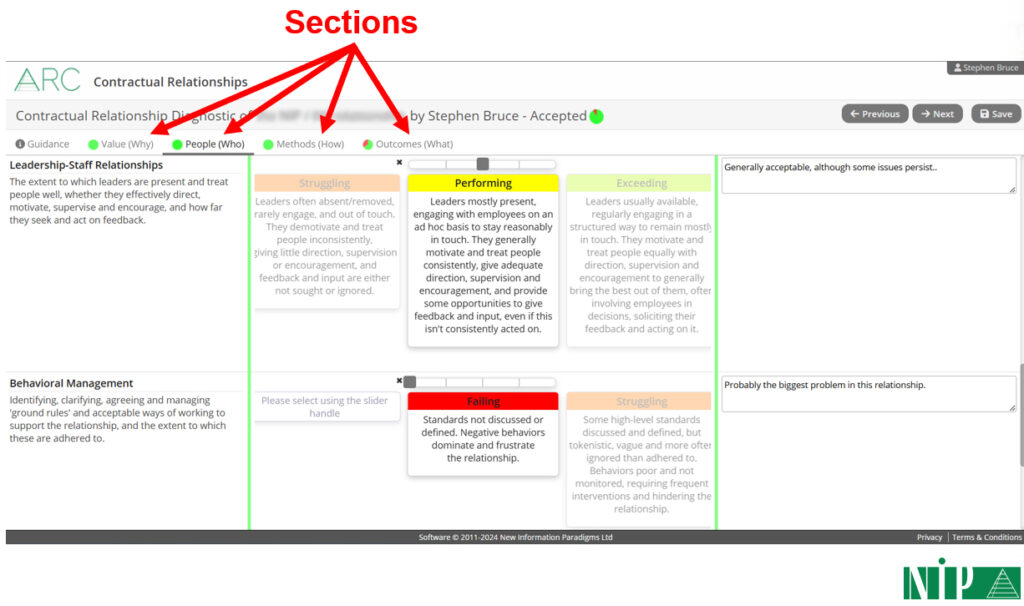

Well, not only do they totally differ from surveys, they naturally support evaluation, with sections grouping related things together, and evaluation then clear and easy to do:

Labels and descriptions are on the left, evaluation statements are in the middle to choose from using slider bars, and there’s then space on the right to enter comments.

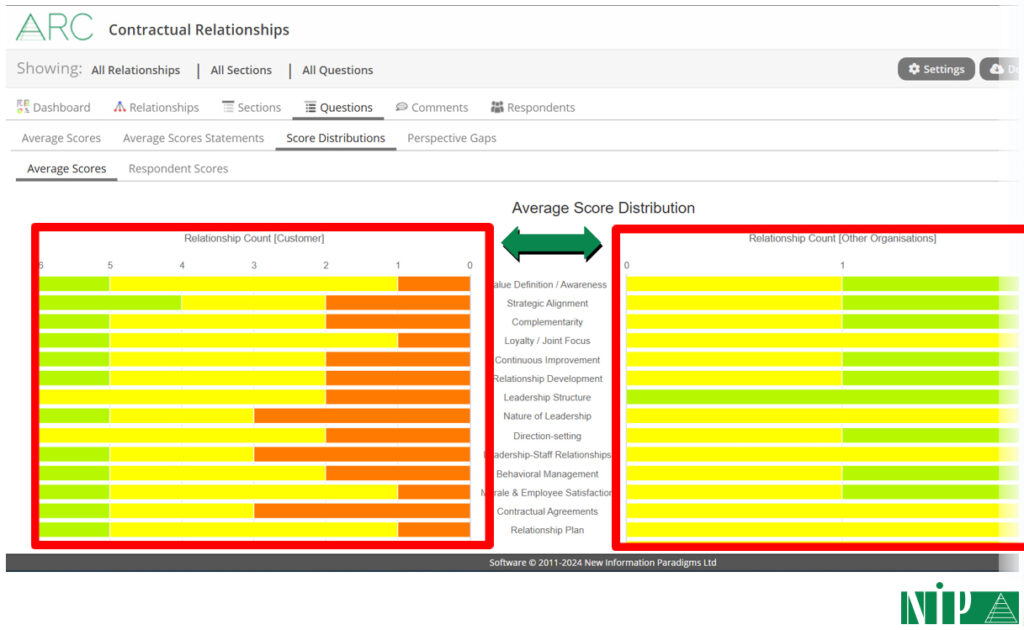

But online Diagnostics are far more than just an intuitive UI; they also readily provide the kind of rich reporting needed to gain insights: overviews, more detail, and – crucially – highlighting the perception gaps I mentioned above, e.g.:

But, in theory at least, you could maybe get this far with Excel, for example, and so it’s scalability that’s perhaps the first unique advantage for online Diagnostics.

This is crucial.

Involving everyone is great for a sense of involvement and responsibility, and for morale, but even more than that, we saw in Part 1 how collaboration between people is essential to harnessing Complexity.

With that “generative constraint” of Value, they give you the bottom-up innovation you need, from the perspective of the front line (which, as we saw in Part 2) can’t be effectively harnessed when it’s left to senior management.

And working online is scalable to any number of participants.

It’s also immediate.

Unlike workshops or interviews for getting inputs (which, as an important aside, also can’t really scale), there’s no scheduling constraints; no writing-up, processing and collating; it just happens automatically.

It’s secure and discreet (we make it anonymous by default), so it’s a safe space to be completely frank: far less “confronting” (for lack of a better word) than workshops or interviews.

It’s therefore inclusive of people with key insights that are more naturally introverted, and also more basically of the majority of people that wouldn’t be at workshops.

So, putting this all together, you can make a start with other methods, but it’s online Diagnostics that are truly transformative.

And indeed, all this is a huge transformation opportunity.

The transformation opportunity

Now, there’s a lot more to say than the scope of this series allows, but as we saw in Part 2, there’s a crucial gap to decisively fill around Value.

Think about it.

Every other aspect of organizational life has a dedicated role or function (HR for human resources, quality, legal, etc), but there’s no Value-focused function.

And someone is going to need to step into this void, with those at the front line and at the hub of key relationships surely ideally placed to step-in to such a role (e.g. contracting and commercial professionals, alliance managers, supply chain managers, etc).

Next, and perhaps more away from the negative, we saw in Part 2 how AI is increasingly taking the lead around execution, so many existing roles need to find a way to focus more on those higher levels if they’re going to remain relevant and valuable to their organizations.

And there’s finally also an urgency here, because the PESTLE challenges we saw in Part 1 are only going to get more intense: business as usual just isn’t an option.

But whoever can take the lead with Value to respond to those challenges, and really own the understanding and managing of it, will not only have a far more fulfilling role; they’ll also be more valued by the business.

If that sounds in any way attractive and compelling to you, I urge you to get in touch to trial a Diagnostic: this is going to be a transformation opportunity for someone – why not you?